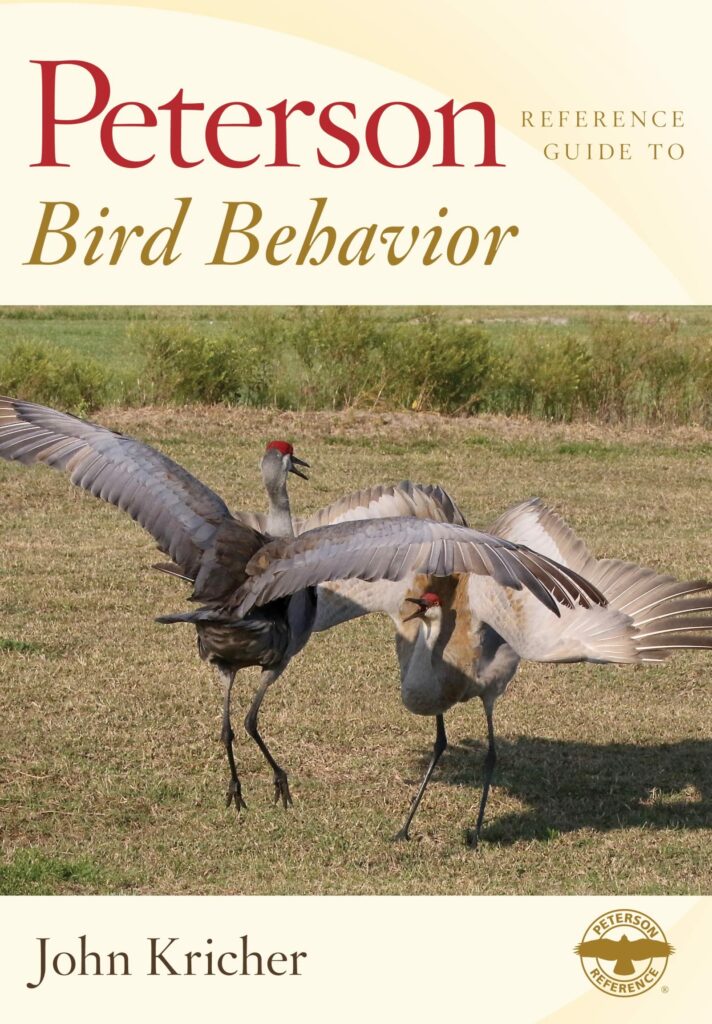

Peterson Reference Guide to Bird Behavior. John Kricher. 2020. Mariner Books, Boston, MA, USA. 360 pages. ISBN-10 : 1328787362. ISBN-13 : 978-1328787361. Hardcover ($27.99).

There is a stereotype of a certain type of birder, sometimes called a lister, ticker, or twitcher, who is only concerned with identification, chasing rarities, and adding new species to a life list, while the behavior and the lives of the birds are unimportant. I don’t know how many birders actually fit that stereotype, but it is certainly true that many birders know little about the behavior of the birds they chase. Even backyard birders might initially know little about the chickadees that are coming to their feeders.

I was once a bit of a lister, but that changed very early in my birding life. When I was 11 years old, growing up in Texas, I was an avid birder, and I was familiar with most birds that I could find in my yard. But then something new showed up, the Pine siskin. Not just a single bird, but a flock of 50 or more all crowding onto the feeders. I was so excited to see something new, but almost as soon as I had added the bird to my life list, I realized that the presence of this bird raised a lot of questions: Why are Pine siskins here this year, but not in years past? Where do they usually live? Why are they simultaneously so highly social, living in a big flock, but also so combative, with wings spread, beaks open, fighting for space? These are questions about behavior. These are the kinds of questions that encourage us to think more deeply about the complexity of the lives of birds.

There have been a surprising number of recent books on bird behavior, including works by David Allen Sibley, Jennifer Ackerman, Wenfei Tong, Barbara Ballentine, & Jeremy Hyman (that’s me). I’m not sure what explains this proliferation of behavior books, but as someone who studies bird behavior, I’m happy to see a focus on the topic. I haven’t read all these books, so I cannot recommend one over another, but they all seem to have their own styles, and their own target audiences. I’ve read reviews of these other books and it seems like some of these books might be more technical, while others for a more general audience. Some of the books include personal anecdotes, some might include the stories of the researchers doing the work, and others might be more purely informational in content.

The Peterson Reference Guide to Bird Behavior, by John Kricher, is a little bit of everything. It’s written in a friendly, conversational style, and is filled with terrific photographs illustrating behavior which should make it accessible to a wide audience. At the same time, it’s never dumbed down and introduces a lot of technical terms and concepts from ecology and evolutionary biology. Kricher’s book is also expansive in its coverage, devoting chapters to basic bird anatomy and physiology (Chapter 3), brains and sensory systems (Chapter 5), feathers and flight (Chapter 8), and bird diversity (Chapter 4). Some other reviews have noted that these chapters result in a substantial proportion of this book not being explicitly about behavior. However, the background provided in these chapters should prove valuable in understanding many aspects of behavior discussed in later chapters. The other chapters cover behavior broadly, including self-maintenance behavior, social behavior, mating and territorial behavior, parental behavior, and migratory behavior.

There is a tremendous amount of interesting information in this book. I’ve been a “professional” bird biologist for several decades now, but I learned a lot reading this book, and I was constantly going online to search for references about some of the facts Kricher mentions. For a general audience, I think this book would provide answers to some of the most common questions I hear about birds, and it will also provide insight into aspects of behavior that the average backyard birder may have never considered.

Beyond the accumulation of facts, the book provides a theoretical framework that helps to explain the ecological and evolutionary basis for behavior. For example, in an anecdote about foraging Yellow-crowned night herons, Kricher points out that bird behavior has been honed by generations of evolution by natural selection and that birds are constantly pitted against both abiotic forces and biotic forces in the struggle for existence. Kricher notes that some aspects of behavior are genetic, others are learned, but importantly, nature vs. nurture is a false dichotomy, and many “genetic” behaviors can be shaped by further learning, and many “learned behaviors” are limited by an underlying genetic template.

Kricher also encourages the reader to focus on individual fitness, rather than considering “good of the species” arguments, and that the goal of increasing lifetime reproductive success can help us understand the sometimes-counterintuitive behavior of parents who may not care for all of their young equally. These are all concepts which I regularly find myself explaining to undergraduates in my classes, and I greatly appreciated including them in a book for a broader audience to help people deeply understand bird behavior.

My criticisms of the book fall into two categories: factual and stylistic. As mentioned above, this book is filled with interesting bird facts, and I frequently consulted the literature to see papers about a new (to me) fact. However, there were also moments where I don’t think the facts were correct. For example, I was surprised to read that in American robins, both sexes incubate the clutch (page 80). Even more surprising was the statement that “once a cowbird juvenile is capable of flight it leaves the host species’ nest at night and associates with roosting cowbirds” (page 269) When I went to the literature to look up more about these facts, I couldn’t find any statements supporting them, but if I missed something, I apologize.

Other factual “errors” were more due to the problem of trying to make general statements that cover 10000 species of living birds. For example, the book suggests that in Passeriformes, songs are learned “usually from the male parent” (page 40). Learning song from the male parent may be true on occasion, but I think the male parent is the tutor in a minority of cases. Another example came up in the discussion of multi-brooded species, when the book states that: “Sometimes birds construct an additional nest for a second brood rather than use the first nest.” but wouldn’t it be more accurate to say that most multi-brooded birds build a new nest for the second brood rather than reuse the same nest?

My stylistic criticisms are merely an opinion, but there were places where I found the book to be a bit disorganized and occasions where the writing was repetitive. For example, there is a discussion of delayed plumage maturation which seems out of place in the chapter on nesting behavior. Some topics are presented in multiple chapters, and on occasion, the same idea is presented more than once in the same chapter or even the same paragraph. These incidents aren’t errors, and repetition can certainly have a valuable instructional purpose, but there were many places where another round of editing might have been useful.

Despite my criticisms, this is an entertaining book which contains information that will enhance a reader’s understanding of bird behavior and inspire a reader to answer questions on their own.

Jeremy Hyman

Professor and Assistant Department Chair

Department of Biology

Western Carolina University

Header photo: Greater Sage Grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus), USFWS/Dave Menke

Suggested citation:

Hyman, J. 2022. Review of the book Peterson Reference Guide to Bird Behavior, by John Kricher. Association of Field Ornithologists Book Review, https://afonet.org/2022/07/peterson-reference-guide-to-bird-behavior/.

If you are interested in contributing a book review, or if there is a book you would like to see reviewed on our site, you can contact our Book Review Editor, Evan Jackson at evan.jackson@maine.edu