https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691255460/avian-architecture-revised-and-expanded-edition Peter Goodfellow. 2024. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA. ISBN 9780691255460. Hardcover ($29.95 USD).

This book examines avian architecture and specifically, seeks to explore how birds design and build. Whilst such architecture primarily takes the form of nests constructed to house their offspring, it also includes the bowers constructed by bowerbirds as part of their courtship displays, and the structures in which some species store food. I am sure that most people reading this review will be familiar with bird’s nests, because many species breed in proximity to humans in their gardens and backyards. Birds construct nests of various designs and in an even greater variety of sites, and this book provides an overview of some of the more interesting nests. These include the mounds built by megapodes, the elaborate nests of passerines, and the huge nests built by raptors, with the coverage of each nest type being enhanced by accompanying case studies and illustrations.

This book is a “revised and expanded edition” of the first edition that was published in 2011. This begs the question of whether a second version is needed or not? I would argue that the answer to that question is a clear yes, because the past decade or so has seen a huge increase in the interest in, and the subsequent academic research focus on, avian architecture and particularly on their nests. The new edition therefore naturally covers some of the most exciting advancements that have been made over the past decade or so. However, it is important to clarify that this book is not aimed at academics and instead, aims to provide an accessible overview for those people interested in avian architecture. There can be little doubt that the author achieves this aim, because it does indeed provide an inspiring account of the wide array of bird’s nests and other forms of architecture.

The book is divided up into twelve main chapters that cover the main nest types. The first chapter covers the scrape nests of species including plovers and terns, and therefore discusses how these nests, which are merely scrapes in the ground and lined with a minimal amount of nest material, have evolved to provide camouflage against predators. Chapter two then goes on to cover holes and tunnels and makes the important distinction between those species that excavate their own tunnels in which to breed, such as great spotted woodpeckers (Dendrocopos major), and those species that occupy previously excavated holes such as black-capped chickadees (Poecile atricapillus). The former choose where to excavate their nest cavities, whereas the later build their nests inside holes excavated by primary cavity nesting species and are therefore heavily reliant upon them for creating their nesting sites.

Chapter four covers aquatic nests which are those built by species such as horned grebes (Podiceps auritus) or common moorhens (Gallinula chloropus) that float on water, meaning that preventing the eggs from drowning is a specific requirement. Chapters 5 and 6 then cover cup-shaped nests and domed nests, respectively. Cup-shaped nests that are built by species including song thrushes (Turdus philomelos) represent a type of nest that requires considerable cognitive abilities to build. Other species, such as cactus wrens (Campylorhynchus brunneicapillus) and long-tailed tits (Aegithalos caudatus), go further and construct even more elaborate nests that have a roof that provides the birds with protection from predators and adverse weather conditions such as excessive rainfall, high winds, high temperatures, and direct sunlight.

Chapter seven then covers those nests made entirely of mud by species including magpie-larks (Grallina cyanoleuca) in Australia and white-necked rockfowl (Picathartes gymnocephalus) in Cameroon. Chapters eight and nine then cover hanging nests and mound nests. Mound nests are those mounds built by species such as Australian brushturkeys (Alectura lathami) who lay their eggs and then cover them with large mounds of earth so that the eggs are developed by the heat generated by the breakdown of organic material within the mound of earth, as opposed to heat generated by an incubating parent. These nest types are comparatively rare when compared to open cup and domed nests, yet they are among the most fascinating nest types, and it was interesting to learn more about them.

Chapters ten, eleven and twelve cover the nests built by colonies and groups of birds, the courts and bowers that serve as courtship behaviours, and edible nests and food stores, respectively. These nests are some of the most intriguing types of avian architecture and I particularly enjoyed reading these chapters. For example, the huge communal nests of sociable weavers (Philetairus socius) represent some of the most impressive structures built by birds. Meanwhile, the bowers built by bowerbirds are undoubtedly an impressive feat of avian engineering, yet it is important to remember that they are used solely for mate attraction. Meanwhile, colonially breeding white-nest swiftlets (Aerodramus fuciphagus) build their cup-shaped nests from their own saliva, meaning that they build their nests using self-produced materials. Their nests are often harvested by local people and turned into birds-nest soup, that has been used as a therapeutic aid for many years and even today, it is considered a delicacy in southeast Asia.

The book is therefore full of information and has many strengths. The first of those is that it is easy to read, and in the process of reading this book, I frequently covered many more pages than I set out to do so, which is testament to how well it keeps the reader interested. This is helped by the fact that there are no references in the main text, which undoubtedly helps its flow. There is, however, a very useful section at the end of the book on “Resources” which outlines interesting books, scientific papers, and websites for people to look at if they wish to do so. This section contains many useful resources, although I would have like to have seen Mike Hansell’s book entitled “Built by animals: the natural history of animal architecture” included. This is because it provides an accessible account of animal architecture although it does focus on animals, and not just birds, and so perhaps that is why it has been omitted.

The book is highly informative and will provide readers with a comprehensive overview of avian architecture. I have examined the evolution and function of bird’s nests for many years now, and I learned a great deal about avian architecture whilst reading this book, and so there can be no doubt that people unfamiliar with avian architecture will therefore also learn an awful lot about the topic. This is an important aspect of the book because the text makes the subject highly accessible, yet informative, which is a tough balance to achieve. Mike Hansell, who is a Professor of Animal Architecture at Glasgow University, UK, is credited in the acknowledgements for reading through the text and his input has undoubtedly helped to maintain a high level of scientific accuracy. This means that readers will rapidly acquire knowledge by reading this book.

The main section of the book is covered by chapters outlining the main types of architecture, such as ‘scrape nests’, ‘aquatic nests’, ‘domed nests’, ‘mud nests’, ‘mound nests’ and ‘courts & bowers’. Those chapters are adorned by numerous case studies that focus on the nests of species building some of the more interesting nests such as ostriches (Struthio camelus), Adélie penguins (Pygoscelis adeliae), cliff swallows (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota) and sooty-capped hermits (Phaethornis augusti). The case studies were relatively short and easy to read, which made them highly informative. They made an excellent accompaniment to the chapters that focused on different types of nests and in many ways, the focus on species helped to make the main types of avian architecture more interesting. For me, then, the case studies were a highlight of the book.

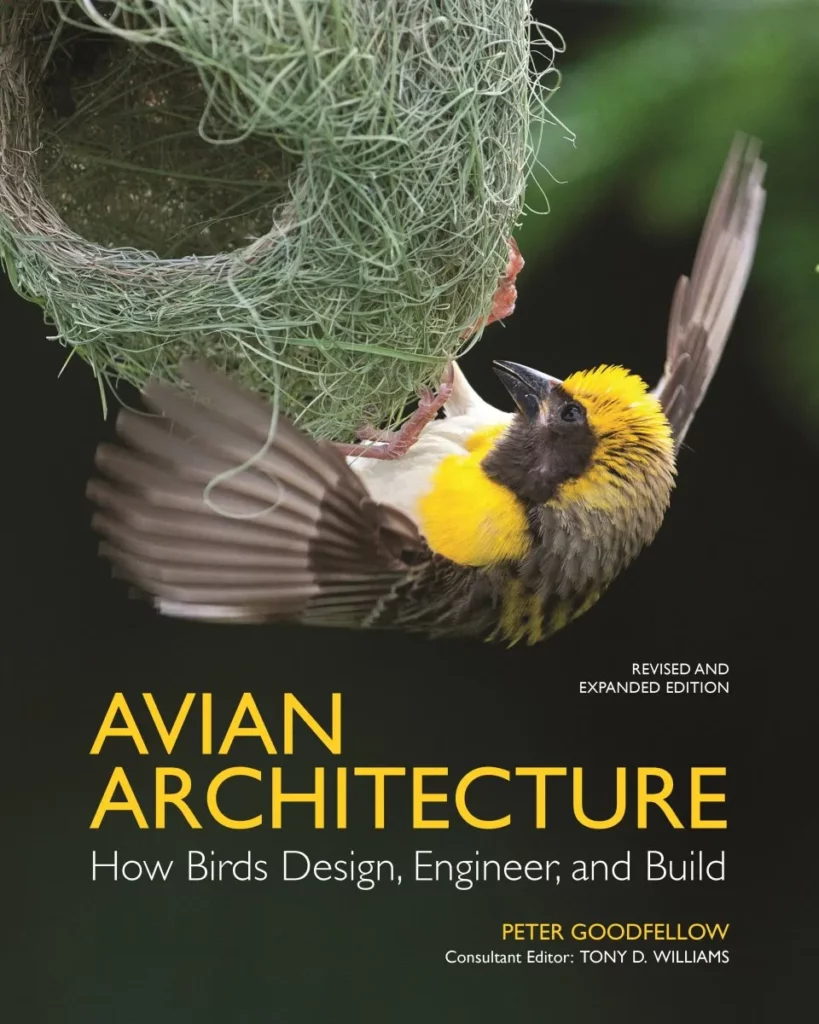

The colour photographs and illustrations that adorn the book are superb and really help to show the reader the diverse array of nests and other forms of avian architecture. A very high proportion of the photographs are visually appealing and as the book is printed on high quality paper, then they look superb. For example, the small yet highly elaborate open cup nest of a hummingbird on page seven looks stunningly beautiful. Meanwhile, the colour drawings that accompany the text are also excellent and really help to illustrate some important points that the author tries to convey. The quality of the drawings is apparent throughout the book as is evident, for example, on pages 126-127 when the incubation behaviours of malleefowl (Leipoa ocellata) are highlighted. The photographs and illustrations are therefore another highlight of the book.

Whilst I am overwhelmingly positive about this book, I do have a couple of very minor quibbles, although it is important to stress that they are only suggestions. First, a relatively small number of bird species such as tree sparrows (Passer montanus) construct ‘nests’ to help them keep warm during the cold winter months at high latitudes, whilst other species, such as sociable weavers (Philetairus socius), build nests which serve both as breeding sites during the hot breeding season and as roosting sites during the cold non-breeding season. It would therefore have been nice to have seen a little more coverage of the use of nests during the non-breeding season as they help protect birds against the cold.

Meanwhile, I would like to have seen more focus on how avian architecture is influenced by human activities in the Anthropocene. For example, avian architecture likely represents an important way in which birds can adapt to changing weather conditions, because nests create a physical buffer between the birds and the wider environment. Illustratively, rufous horneros (Furnarius rufus) and great kiskadees (Pitangus sulfuratus) built large, enclosed nests in the southern hemisphere and prevent their nests from over-heating by orientating the entrance holes of their nest’s southwards, and thus away from direct sunlight, in hotter years. Meanwhile, many bird species are known to include anthropogenic material, such as sweet wrappers and baling twine, into their nests, and it has been shown that such material increases the predation rates upon those nests, possibly by making the nests more obvious to predators. These topics may well have been outside the scope of the book, but it may have been interesting to consider how avian architecture is influenced both directly and indirectly by such human activities.

In summary, then, this book provides a wonderful overview of the wide range of architecture that birds construct. I would therefore thoroughly recommend that anybody with an interest in birds, or wildlife more generally, reads this book. It is reasonably priced, especially given that it is printed on very high-quality paper, which in turns makes the photographs and illustrations highly attractive. Meanwhile, the text is easy to follow and is complemented by the illustrations and photographs that together provide readers with a huge amount of information. This is crucial because readers will undoubtedly obtain a huge amount of knowledge about avian architecture and acquire a new appreciation bird’s nests and other forms of architecture.

Dr. Mark C. Mainwaring

Lecturer in Global Change Biology

School of Environmental and Natural Sciences,

Bangor University,

Bangor, UK

Header photo: Asian Golden Weaver (Ploceus hypoxanthus). Photo by pichaitun via Getty Images.

Suggested citation:

Mainwaring, M. Review of the book Avian Architecture Revised and Expanded Edition: How Birds Design, Engineer, and Build by Peter Goodfellow. Association of Field Ornithologists Book Review. https://afonet.org/2024/06/avian-architecture-how-birds-design-engineer-and-build/.

If you are interested in contributing a book review, or if there is a book you would like to see reviewed on our site, you can contact our Book Review Editor, Evan Jackson at evan.jackson@maine.edu