I awoke in my tent before dawn and heard the first songs of the day beginning to permeate the forest. My dog lifted her head and gave me a look of bewilderment that seemed to say, “these jabbering birds are clearly doing just fine since last year’s drought, let’s go back to sleep.” As tempting as that might’ve seemed, I put on my boots and picked up my recorder instead.

Less than a year prior, in the fall of 2016, I was beginning the second year of my PhD. I’d recently joined the lab of my advisor, Nicole Creanza, to study birdsong evolution. The Creanza Lab broadly studies cultural evolution—the evolution of learned behaviors—using both human language and birdsong as model systems. In my first project, I performed a large-scale comparative analysis of birdsong using song feature data that I compiled from published sources. This project made me realize the incredible range and diversity of songbird vocalizations and sparked a question that has driven my research ever since: how did these vocalizations diverge so wildly, and what does the fact that Oscine songs are learned have to do with it?

Around the same time, I learned about the developmental stress hypothesis of birdsong as an honest signal of fitness in songbirds, which is based on findings across several species that show that stress during development can impede song learning.

While phenotypes in a population are constantly undergoing minor changes as individuals have varied success from year to year, major shifts in population phenotypes can happen far more rapidly under extreme conditions. I wondered, could a similar phenomenon occur in a culturally transmitted phenotype such as song? Specifically, if a stressor was effectively applied across an entire breeding songbird population simultaneously, such that virtually all juveniles experienced impaired learning, would there be a detectable perturbation in population song in the next breeding season? If these juveniles’ songs became the models for future generations, could such a punctuated stressor ultimately induce a lasting change in a population’s—or a species’—song?

Since we knew that detecting potential changes in songs across a population would require many recordings over an extended period, we identified two main ways to test this hypothesis: with a captive population or a natural experiment. For the latter, an environmental stressor would need to occur in an area with ample prior song recordings, either from a long-term field site or public recordings from community scientists.

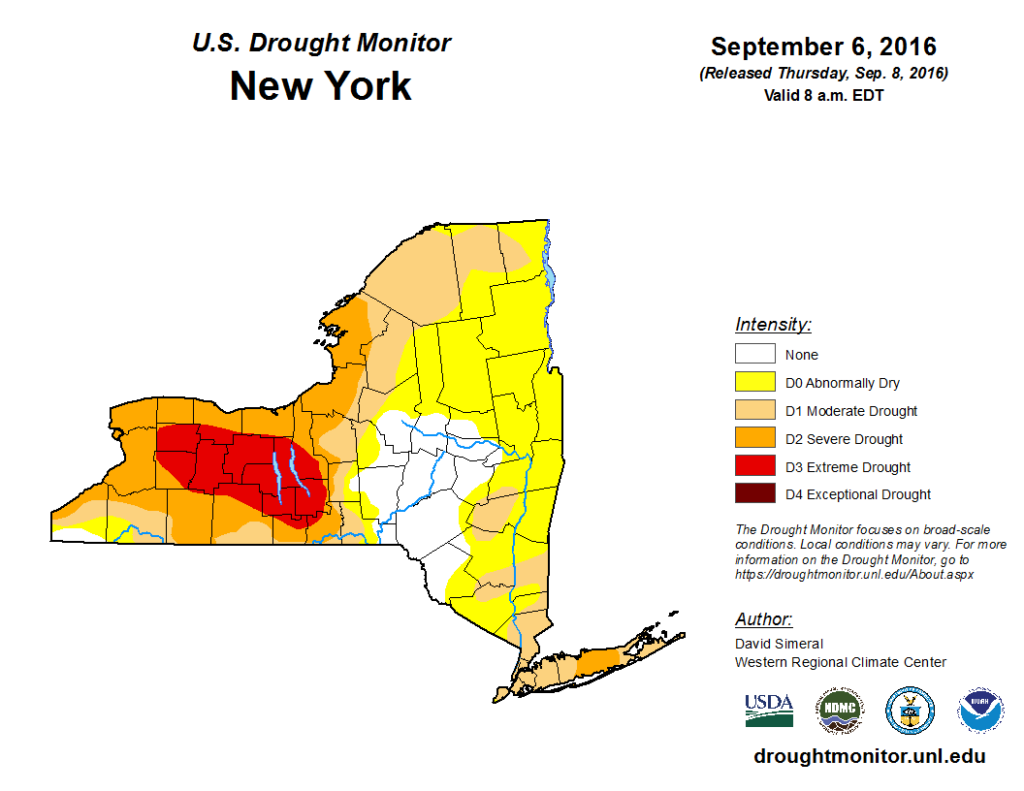

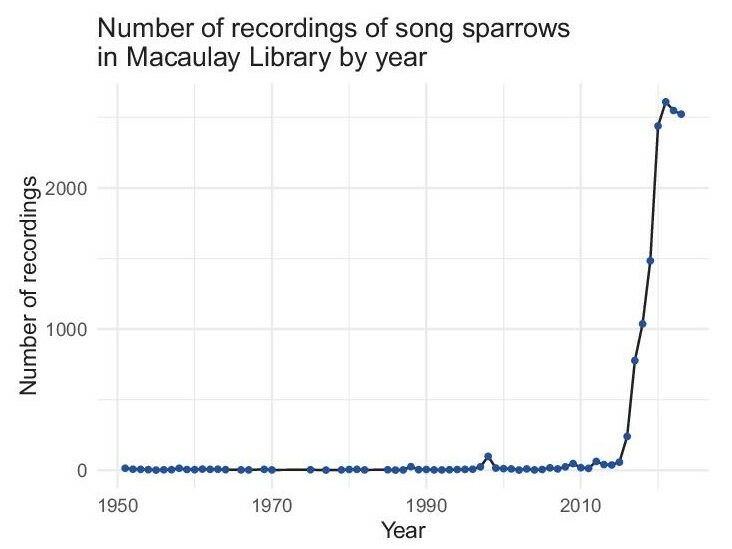

We didn’t have access to a captive population or data from a long-term field site, but our lab was starting to work with repositories of field recordings like Macaulay Library and Xeno-canto, so I looked for regions with an extraordinarily high density of recordings. In Macaulay Library in 2016, there was one area that stood out – the region around Tompkins County, New York, the home of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. The next step was figuring out if an extreme environmental stressor had ever occurred there, and whether it was recent enough to have enough recordings before and after the event to detect possible changes in song features. It was a moment of surreal serendipity when a simple Google search for “New York drought” came back with multiple news articles only a few months old that revealed that a large area of New York state, including Tompkins County, had just that summer experienced a drought that was unprecedented in recorded history for the region.

We preferentially considered species for study that (a) had a large number of publicly available song recordings, (b) had some evidence of site fidelity, and (c) have diets that would likely be impacted by drought. One potential challenge is that severe environmental stress often results in members of a population simply abandoning reproductive behaviors. In the context of this study, this would mean that there would be fewer juveniles developing during the height of the drought, and thus a minimal effect on the represented songs the following years. However, the timing of the drought might have mitigated this challenge: since the drought did not begin until mid-summer, many species would likely have already bred and raised chicks to at least fledgling age, increasing the likelihood that enough juveniles were exposed to drought stress to significantly affect population song.

The species that best fit were the dark-eyed junco (with relatively simple songs) and the song sparrow (with more complex songs). We requested the available recordings from the region from the previous decade and I (and my dog, Moki) spent a week in the summer of 2017 making targeted recordings in central-western New York with a homemade parabolic recorder to bolster our sample size in the year following the drought. We enlisted the help of an undergraduate researcher, Maria Sellers (now pursuing a PhD in biological anthropology), who meticulously quality-checked over 750 individual recordings, extracted bouts of song, parsed the individual syllables using our lab’s software, “Chipper,” and learned to analyze the data in R over the course of her undergraduate career.

Our results revealed a change in the songs of song sparrows, but not dark-eyed juncos, suggesting a fascinating hypothesis: that birds with more complex songs might have a greater chance of being affected by acute widespread stress than birds with simpler songs. This makes sense in the context of song learning and developmental stress, but our relatively narrow scope means that follow-up research is needed to determine whether stress was a direct cause of the changes we observed, as well as how consistent or widespread this phenomenon may be across populations, species, regions, or types of stressors.

This study was also a lesson about both the importance of community science data and the challenges of acquiring experimental and control data from a repository after an environmental stressor has occurred. Our main challenges were that there were relatively few recordings from before the 2016 drought that we could use to compare to post-drought recordings, and there were very few regions outside of the extreme drought zone where there were enough recordings spanning the same time period to act as a control. However, we are optimistic about the future in this regard; the number of recordings deposited to publicly available repositories seems to have skyrocketed in the past several years, with better and better audio recording technology finding its way into our pockets via smartphones. Future studies should thus be much better equipped to further probe the link between stressful climatic events and cultural evolution in songbirds.

Kate Snyder

Postdoctoral Scholar

Department of Biological Sciences

Vanderbilt University

The results of this study were recently published in the Journal of Field Ornithology:

Snyder, K. T., Sellers, M. L., & Creanza, N. (2024). Cultural shifts after punctuated environmental stress: a study of song distributions in Dark-eyed Junco and Song Sparrow populations. Journal of Field Ornithology, 95(2). https://doi.org/10.5751/JFO-00442-950203.

Header photo: Dark-eyed Junco (Junco hyemalis) by tacojim | Getty Images.