Colonial nesting, though prevalent in only a small number of bird taxa, has long fascinated evolutionary biologists, tempting the question: why did it evolve? One approach towards explaining the evolution of avian coloniality employs the ‘cost-benefit’ approach, which attempts to take into account the net effect of all the seemingly important variables. At the nesting site, these can be the benefit from enhanced defence minus the cost of increased attraction of predation (net effect on vulnerability to predation), the benefit of increased access to mates minus the cost of increased competition for them (net effect on mating opportunities) and the increased opportunities to exploit or disrupt neighbors (for example, to steal nest material or food) minus the increased degrees of interference perpetrated by neighbors (including killing of chicks). All in all, inmates of a nesting colony have to be ever-vigilant not just against threats from outside the colony (environmental vigilance) but also from within (social vigilance).

The Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala) – a colonially nesting stork is a good model to explore questions of avian coloniality. In India it is fairly common and nests in either tall trees in villages or (usually) on clumps of trees on islands located in marshes and village tanks, including ponds in urban premises. We employed camera surveillance techniques to explore how rates of environmental and social vigilance in Painted Stork nesting colonies in North India related to multiple factors, such as human presence and predators in their vicinity, number of neighbours (surrogate of colony size), nest height, and nestling age.

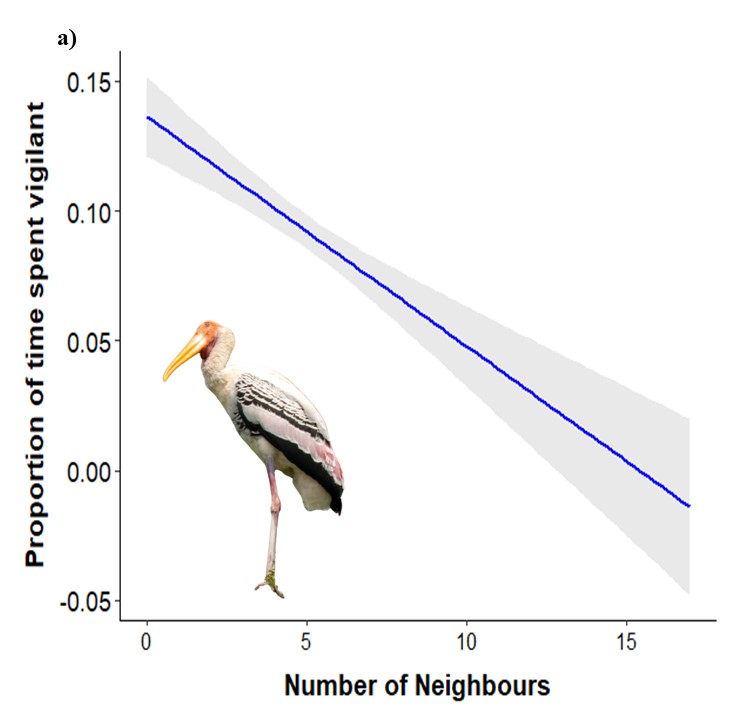

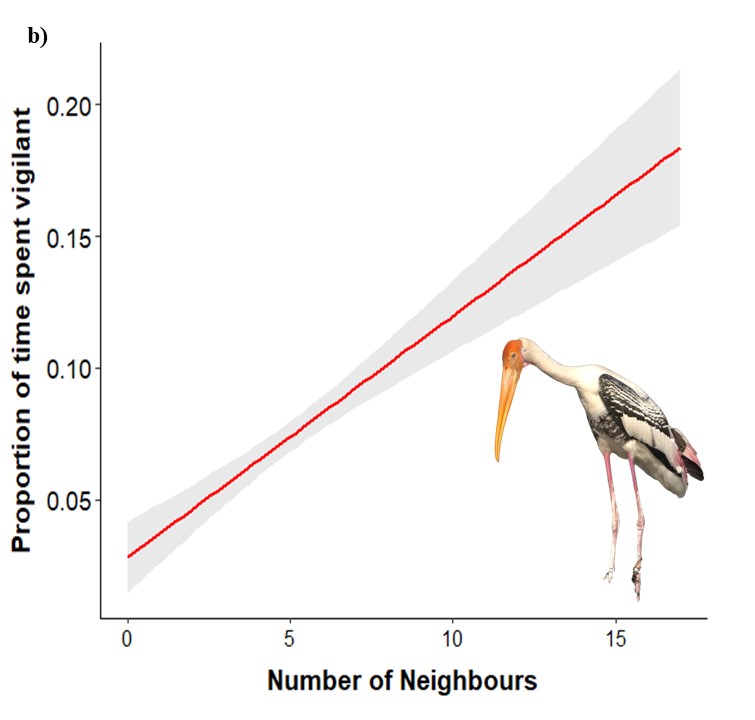

From the video recordings it was possible to discern between the two types of vigilance behaviour exhibited by Painted Stork (see graphical diagram). Our results on how vigilance rates associate with number of neighbours are interesting from the point of view of avian coloniality. A negative relationship between neighbors and ‘environmental vigilance’ was observed (see graphical diagram ‘a’) which is a pointer towards the “many-eyes hypothesis” whereby birds in the nesting colony could benefit from early predator detection in larger colonies. The more eyes there are, more are the chances of a predator or a cause of disturbance being detected and so the burden of being vigilant on each colony resident is much less. However, when it came to ‘social vigilance’- the topic explored in our recent paper in JFO, the opposite trend was observed. Interestingly, vigilance rates increased as the number of neighbours increased (see graphical diagram ‘b’) and this could be likely due to competition, resource monitoring, and intraspecific conflicts. As the group size (number of neighbours) increases, individuals tend to indulge more often in keeping a watch on what their neighbours are doing, in case some of them may happen to harbour evil intentions and pose threats which may impact fitness.

In Painted Stork colonies, social vigilance is likely to arise from two key factors: defence against neighbors in densely packed colonies and gathering information on resources. We have observed that early in the nesting season, competition for territories and mates is intense and it is at this time when storks direct their aggression against their con-specifics in the locality, sometimes fighting bitterly over nesting site, nesting material, potential mates etc. However, they may also monitor their neighbours movements to assess food and nesting material availability.

Though our studies provide some insights about the factors which may shape coloniality in this species we need to do more follow up studies and there is no dearth of interesting questions to ask. For starters, why is it that some species of waterbirds are colonial in some situations and solitary nesters in others? Does a sharp distinction exist between passive coloniality and active coloniality? And many more!

Abdul Jamil Urfi & Paritosh Ahmed

Department of Environmental Studies,

University of Delhi,

New Delhi 110007, India

ajurfi@es.du.ac.in

The results of this study were recently published in the Journal of Field Ornithology:

Ahmed, P., and A. J. Urfi. 2025. Keeping a watch on neighbors: social vigilance in Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala) nesting colonies. Journal of Field Ornithology 96(2):6. https://doi.org/10.5751/JFO-00630-960206.

Other works cited above:

- Ahmed, P & A.J. Urfi* (2024) Environmental drivers of vigilance behaviour in painted stork (Mycteria leucocephala) nesting colonies. Sci Rep 14, 28498. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-78276-8.

- Urfi, A.J. (2024) The Painted Stork: Exploring Ecology and Conservation in India. Pelagic Publications, London, UK.

Header photo: Painted Stork (Mycteria leucocephala) colony in Thailand by cowboy5437 | Getty Images.