Many bird species, like humans, have distinct regional dialects. A New Yorker may refer to a midday meal as “lunch”, but in the south that meal is “dinner”. Likewise, the song of a Common Yellowthroat in the east may sound very different from one in the west. Among birds whose songs are learned, rather than innate, these sorts of regional differences are relatively common and there is considerable research devoted to mapping these dialects and understanding how they arise, persist, or change over time.

While interesting in itself, understanding where different dialects occur can also provide tools to study important aspects of a species’ natural history. For a species that sings both on the breeding grounds and in migration or during winter, one can use the location and timing of these dialects to understand how and where certain populations migrate between breeding and wintering areas. This sort of migratory connectivity information can be extremely helpful to conserving a declining species by revealing whether key challenges are occurring in the breeding area, wintering grounds, or at migratory stopover points.

When dialects differ enough that females develop a strong preference for one over another, this can prevent interbreeding and contribute to a process that may lead to a new species (one of those dreaded “splits”). Ruby-crowned Kinglets have a wonderful, bubbly song that can be remarkably loud for such a tiny bird.

This kinglet sings enthusiastically during the breeding season, but also sings on migration and, to a lesser extent, in winter. They breed in the northernmost Midwest, from eastern Canada through Alaska, in most of the western mountains, and either migrate through or winter in nearly every part of North America.

Because no one had studied regional variation in this delightful song, we decided to use the huge and growing collection of archived song recordings available from xeno-canto and Mark Robbins/Macaulay Library to investigate this topic.

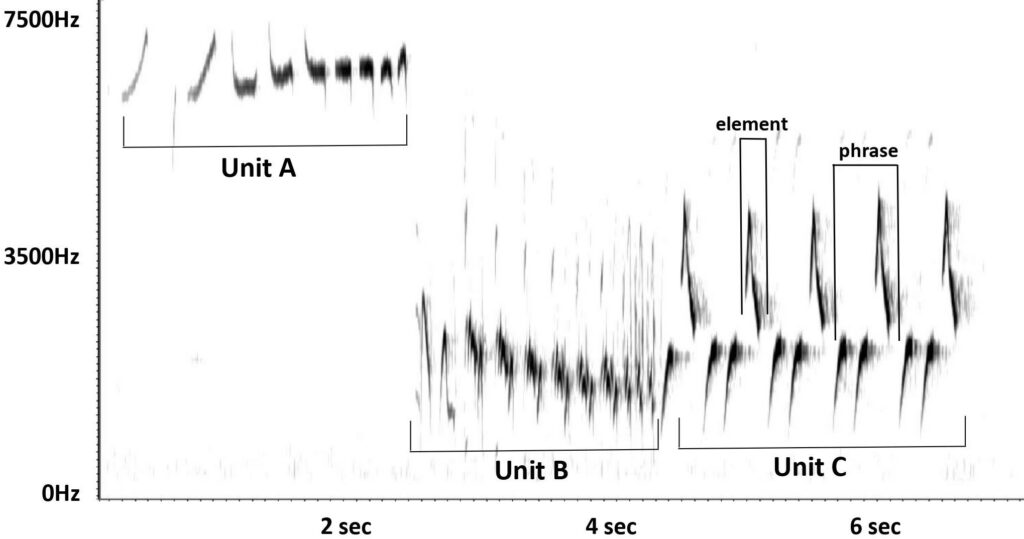

We chose to focus on the phrases that make up the last part of this birds’ three-part song (labeled Unit C) as this is often the loudest and most distinctive part of this kinglet’s song.

We found that individual Ruby-crowned Kinglets use only a single phrase type and that certain phrase types dominated in different regions of the breeding range. In each area, 2 or 3 phrase types were used by most birds in that region and those phrase types were rarely, if ever, heard in other regions. For example, east of the Great Lakes area to the Atlantic coast two phrase types dominated and were heard nowhere else:

In the Rocky Mountains of Colorado, nearly every kinglet used one of these two phrase types:

In the interior of Alaska, a single phrase type was used by more than 70% of all birds recorded there:

A non-migratory subspecies of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet breeds along the Pacific Coast from Alaska through British Columbia and 21 of the 22 individuals recorded there used one of two phrase types and those two types were not observed anywhere outside that range:

Now that the dialects have been mapped, an analysis of songs recorded during migration and winter can reveal where the various populations of this kinglet winter, and what routes they may take to get there. And this can be done with no need to capture and tag birds.

We are particularly interested to see where birds that breed in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California spend their winter, as this population appears to have suffered very significant declines since the early 20th Century and their wintering location is unknown.

The results of this study were recently published in the Journal of Field Ornithology:

Pandolfino, E, R., and L. A. Douglas. 2022. Regional song dialects of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet. Journal of Field Ornithology 93(2):6 [online] https://doi.org/10.5751/JFO-00120-930206

Header photo by Mike Budd/USFWS