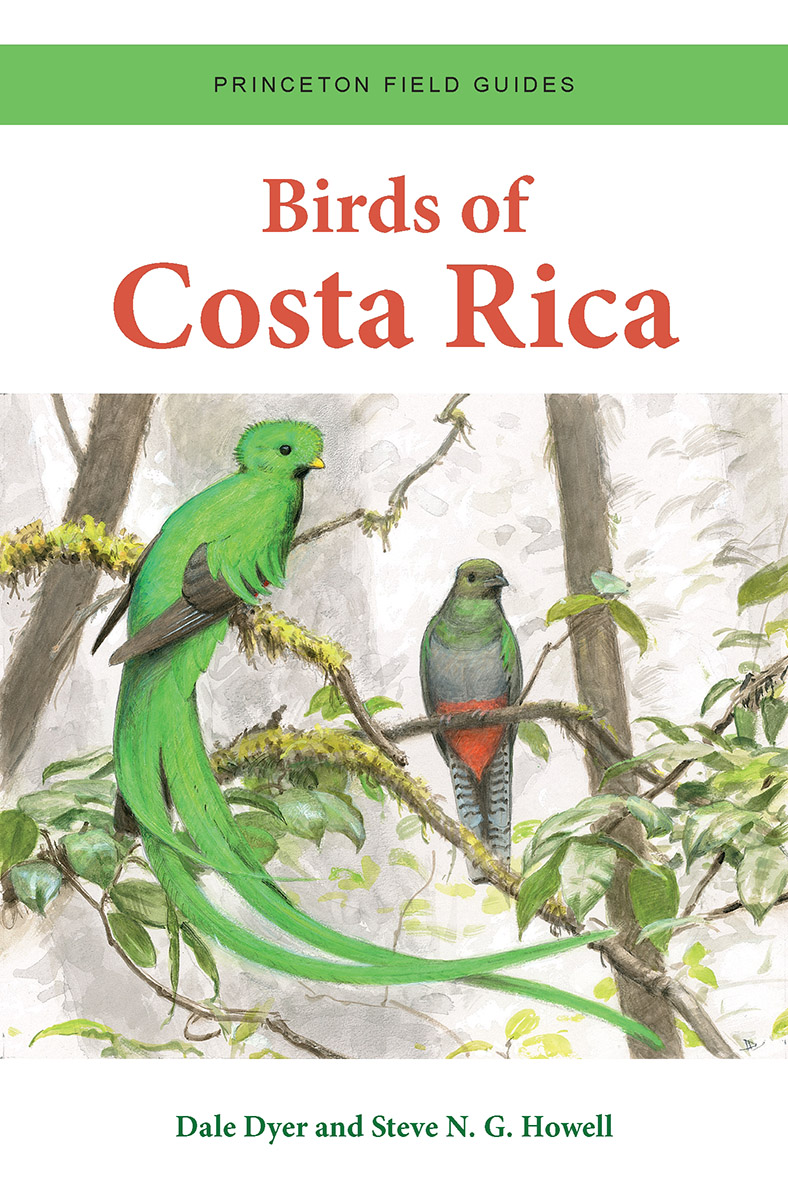

Birds of Costa Rica. Dale Dyer and Steve N.G. Howell. 2023. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, USA. 456 pages. ISBN 9780691203355. Paperback ($29.95 USD).

Costa Rica is a hotspot of avian diversity, and not surprisingly both ecotourists and scientists flock to this small Central American country to observe and study its birds. This new field guide to the birds of Costa Rica will doubtless become the standard reference for the country, and offers a more streamlined and navigable product than the previous Birds of Central America (2018), also illustrated by Dale Dyer. The authors have extensive experience developing field guides and it shows. Birds of Costa Rica (2023) is beautifully illustrated and packed with in-depth, relevant information. It offers several notable improvements over The Birds of Costa Rica (2014) by Garrigues & Dean, which has served as the standard guide for many years: it provides more up-to-date species taxonomy, more detailed species accounts, and in many cases better illustrations.

Like most field guides, Birds of Costa Rica (2023) opens with a section detailing how to use the book. This is concise and well-written, providing detailed discussion on scope, the format, content, and terminology of accounts, general bird anatomy, and Costa Rican geography. Early on the authors include maps of four common distributional patterns of bird species (humid lowlands, dry lowlands, foothills, and highlands), which are particularly useful for users who are not familiar with Costa Rica’s topography, or ecotourists planning a vacation to hit the major biome types. This is followed by a brief but illuminating section describing the country’s biogeography and how its physical geography influences local climate to create the general patterns where birds are found. The biogeography section includes brief descriptions of the wide variety of habitats found in Costa Rica along with a collection of 20 color photographs depicting how they appear on the ground. These provide readers with valuable visual context for habitats later referenced in the book.

The authors are exceptionally transparent in their treatment of bird systematics. The authors generally rely on the 2021 IOC taxonomy as a baseline, but attempt to include alternative taxonomic labels arising from scientific uncertainty or newly proposed species splits where appropriate. Where taxonomic ambiguity exists, they helpfully include alternate species names in parentheses and uncertain labels or proposed splits in brackets, while providing evidence for the changes in the appendices. While they admit this to be somewhat cumbersome, we find it is a much better alternative than simply overlooking these uncertainties or exclusively relying on a single nomenclature which may be unfamiliar to users and potentially become outdated in the near future. The discussion of taxonomic uncertainty and the reasoning behind species labels is forthright and provides readers with a candid understanding of how decisions were made. The choice to preemptively include some expected changes is wise, allowing better understanding of birds in the region, and will likely increase the longevity of this guide. As systematics marches ever (sometimes frustratingly) onwards, more field guides that demystify the authors’ decisions on species naming, and connect present names with those of the past and future would be welcome.

The rest of the book is devoted to species accounts, providing color illustrations and written descriptions for over 800 species with distribution maps for all those that are likely to be encountered on the mainland, inshore islands, or nearby marine waters. Additional species from Cocos Island and a list of rarities, vagrants, and offshore visitors are included in the appendices, offering solace to completionist readers. The authors list species in the traditional field guide order, rather than phylogenetic order, and organize the plates so that similar species appear close to each other when possible, making the guide intuitive and user friendly. Additionally, the pictorial table of contents of the major bird families on the inner cover and first few pages of the book is a clever addition that facilitates quickly finding species in the field.

The species accounts themselves are engaging and provide rich descriptions of bird habitat, behavior, identification marks, near species comparisons, vocalizations, and regional status. Steve N.G. Howell’s portrayal of behavior is particularly detailed for many birds, pointing out specific behavioral cues that are useful for identification in the field and making them come alive for the reader at home. Concise, yet informative accounts of families, species groups, and occasionally genera are also a welcome inclusion. Unlike many bird guides, some natural history details of the birds are teased in the text, giving greater ecological depth to the accounts. For example, on pp 314 the authors describe a set of unrelated but similar-looking flycatchers likely all being mimics of the foul tasting Great Kiskadee. Inevitably these details leave the reader wanting more, and saddened that this concise guide is space limited (Why and how does the Great Kiskadee taste foul? How do we know? Did the authors taste it? Should I?). Species’ distribution maps are quite generalized but including San José and gridlines on each map improves interpretability.The illustrations by Dale Dyer are excellent overall, showing great attention to detail and artistry in depicting key identification marks while making the representations feel dynamic and lifelike. The illustrations of hummingbirds on pp. 213-233 offer a particularly good demonstration of these strengths, clearly depicting key details in a wide variety of the different postures these birds are often seen in. Dyer’s illustrations are generally smoother and depict softer plumage colors and textures than the Garrigues & Dean (2014) guide (which emphasizes strong color contrasts and plumage patterns that can be difficult to discern in the field). This naturalistic style offers a more faithful impression of how birds are likely to appear during field observation, especially when taken together with the details on identification provided in the written accounts. In addition to the primary species depictions, the authors include a number of comparison illustrations featuring possible misidentifications (e.g., white herons in flight, pp. 79; sphinx moth versus hummingbirds, pp. 223) as well as in situ illustrations depicting bird appearance in common behavioral situations (e.g., Sungrebe in flight, pp. 39; Potoo nocturnal eyeshine, pp. 153; Great Green Macaw in flight over habitat, pp. 178). These artistic flourishes are a delight. The book does include an index of English names, but unfortunately does not contain a corresponding index of scientific names, or a complete list of birds of Costa Rica organized by taxonomic family. Both would have been helpful for the scientific user of this guide. Despite these minor omissions, which can hopefully be addressed in the future, Dale Dyer and Steve N.G. Howell’s Birds of Costa Rica (2023) is an exemplary field guide and a rich source of information on Costa Rican birds that is accessible to a wide range of users. We anticipate that it will become the guide of choice for many years to come.

Luke Owen Frishkoff

Biology Department

University of Texas at Arlington

Evan Matthew Mistur

Department of Public Affairs and Planning

University of Texas at Arlington

Header photo: Fiery-throated Hummingbird (Panterpe insignis) Levi Novey/USFWS

Suggested citation:

Frishkoff, L, and Mistur, E. Review of the book Birds of Costa Rica by Dale Dyer and Steve N.G. Howell. Association of Field Ornithologists Book Review. https://afonet.org/2023/07/birds-of-costa-rica/.

If you are interested in contributing a book review, or if there is a book you would like to see reviewed on our site, you can contact our Book Review Editor, Evan Jackson at evan.jackson@maine.edu