The ability to attach devices such as satellite transmitters or geolocators to birds has transformed our knowledge of how birds migrate. However, these technologies have their limits. They require capturing the birds, usually twice, and the expense limits most studies to a small number of individuals within a relatively limited portion of their range. Also, some species, such as the Ruby-crowned Kinglet, are too small to allow tagging with current geolocators.

For birds that use distinctly different song dialects in different parts of their breeding range (which is the case for many, perhaps most, songbirds), there is an alternative approach that does not require capturing a bird and can be used to study huge numbers of individuals on a continent-wide scale. This method can be applied to any such species that also sings during migration or in winter. Once the locations of these breeding range dialects have been mapped, one can use songs recorded during winter or migration to map the movements of these populations. And now that we have access to the enormous and rapidly growing archives of recorded bird song from sites such as xeno-canto (www.xeno-canto.org) and the Mark Robbins/Macaulay Library (www.macaulaylibrary.org), this method becomes more practical with each passing year.

To our knowledge, this powerful and efficient technique has only been applied to four species. In 1995 DeWolfe and Baptista used this approach to study the migration strategy of a subspecies of the White-crowned Sparrow. More recently, we have applied this to the migration strategy of the Golden-crowned Sparrow, the source of irruptive breeding populations of the Black-chinned Sparrow, and now, the migration patterns of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet.

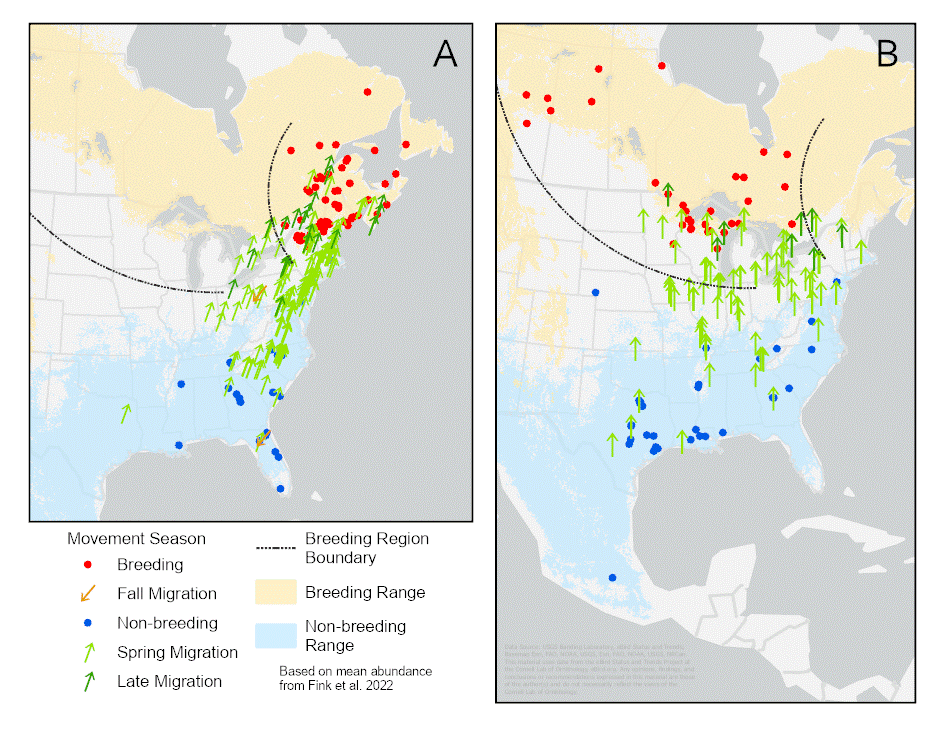

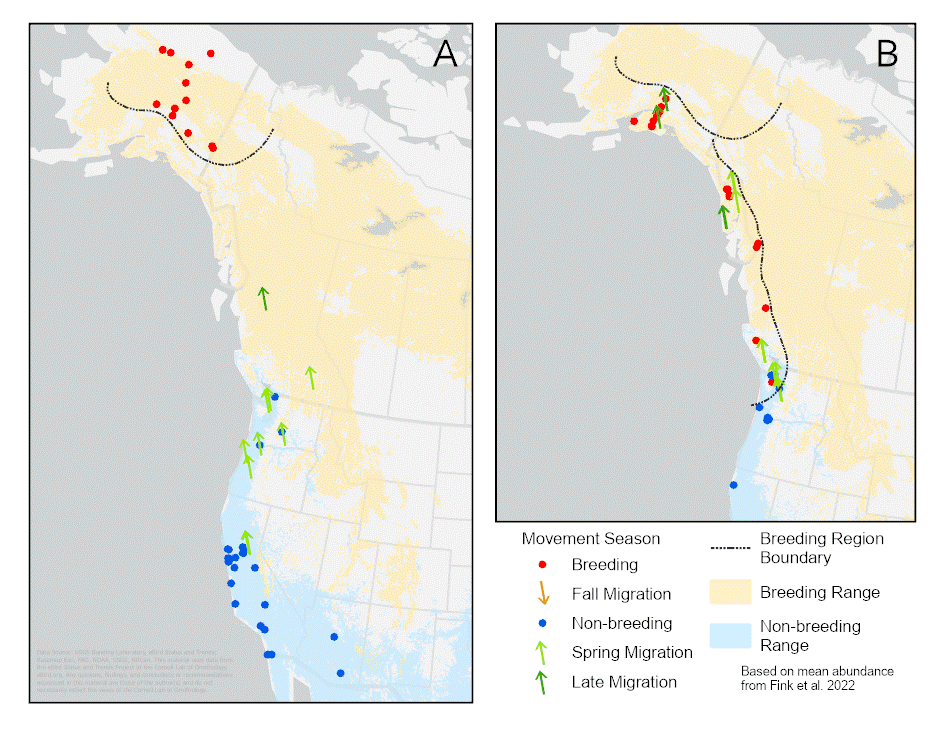

The Ruby-crowned Kinglet’s year-round range encompasses nearly the entire North American Continent. This bird breeds from Alaska across Canada, into New England, and in most of the montane west. Different breeding populations have shown dramatically different abundance trends. We had previously mapped the locations of the dialects of the Ruby-crowned Kinglet on the breeding range and wanted to use that information to determine the winter ranges and migration pathways of these populations to see if different conditions along the migration routes or on the wintering grounds might help explain these contrasting trends.

Using non-breeding season song recordings from nearly 500 individuals throughout the range, we were able to determine the wintering range and general spring migratory patterns of some of the various dialect populations (Figures 1 and 2). Unfortunately, we were unable to determine the winter ranges of the Rocky Mountains or the Sierra Nevada-Cascades range breeders. These populations most likely winter in Mexico and, to date, there are very few archived song recordings from that area. A concerted effort from birders and researchers to record Ruby-crowned Kinglets in Mexico could help us understand the reasons for the starkly contrasting population trends of this species which is thriving in the Rockies and now rare and sparsely distributed in the Sierra Nevada.

Edward Pandolfino

The results of this study were recently published in the Journal of Field Ornithology:

Pandolfino, E. R., and L. A. Douglas. 2023. Using song dialects to reveal migratory patterns of Ruby-crowned Kinglet populations. Journal of Field Ornithology 94(3):10. https://doi.org/10.5751/JFO-00315-940310

Header photo: Ruby-crowned Kinglet (Regulus calendula). Photo by Jacob W. Frank/NPS.