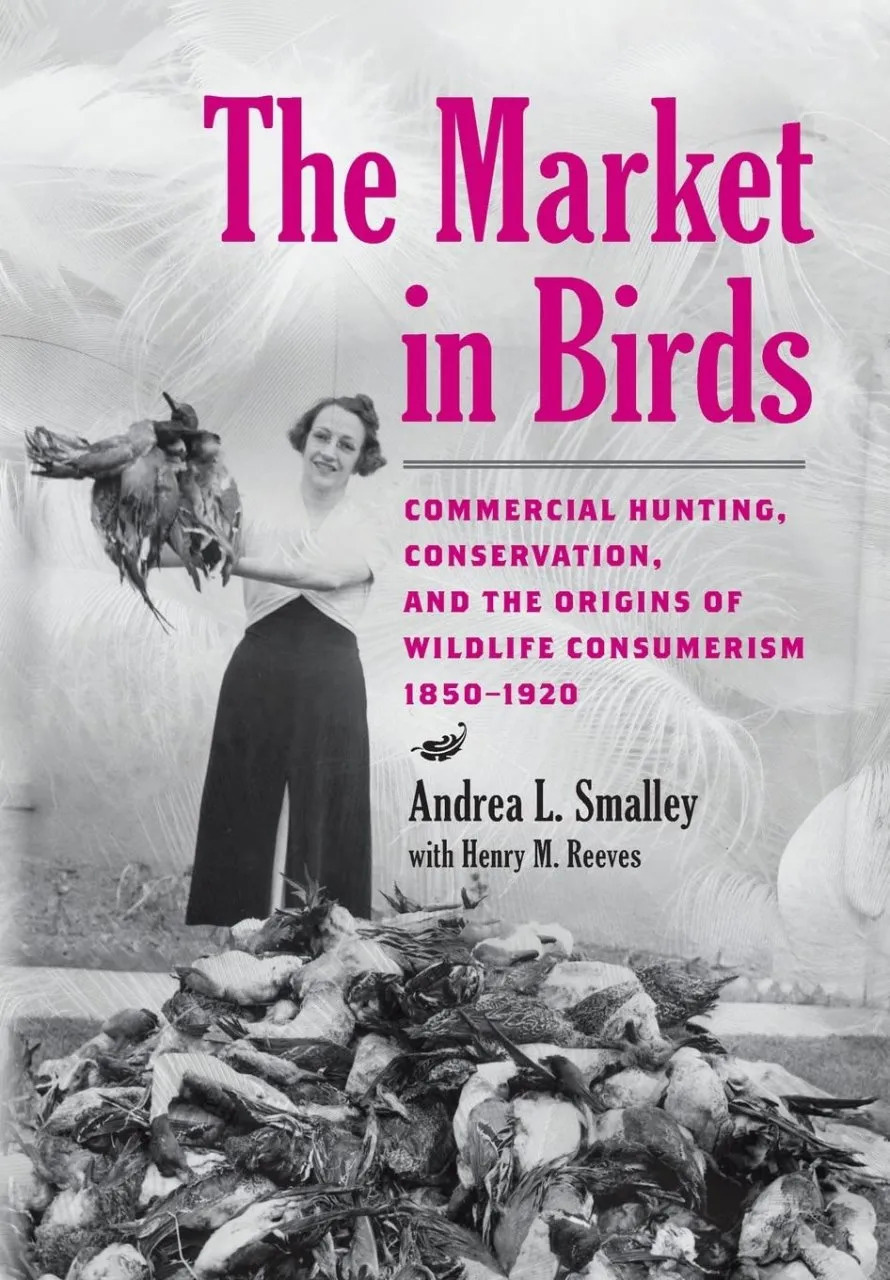

The Market in Birds: Commercial Hunting, Conservation, and the Origins of Wildlife Consumerism 1850-1920. Andrea L. Smalley with Henry M. Reeves. 2022. Johns Hopkins University Press. Baltimore, MD, USA. 320 pages. ISBN 9781421443409. Hardcover ($59.95). Available as an Ebook and online via Project MUSE.

As I read The Market in Birds, I found myself drawing Venn diagrams. I have multiple partially overlapped circles, trying to sort out the convergence zones of “hunters vs. conservationists” or “sportsmen vs. naturalists.” Some of my diagrams became complex puzzles, like the one sorting out how much overlap there might be between people who: like birds; like “nature”; like being outside; and like money. This strange chimera of a book ends up clarifying only some of these relationships by its end. It also stubbornly refuses to engage on some other, basic questions, though it tells a compelling, disturbing, and at times, madcap tale of the rise and fall of the commercial market for wild birds and their assorted parts. This traffic in birds arose in the late 1800s, and was over by 1920 with the passage of multiple federal regulations constraining or outlawing it. This timeline aligns with industrialization and urbanization, and the mass sale and consumption of birds seems less a unique phenomenon, and more a specific example of the myriad ways humans and the more-than-human world got caught up and ground through the machine of capitalism. After all, the innovations that made a continental-scale market possible for wild birds were the same ones that allowed farmers to sell produce grown in the Midwest to rapidly growing cities in the East: the expansion of railway systems, the development of refrigeration and refrigerated rail cars, and ready markets (with ready cash) of urbanites in the Northeast who no longer farmed or hunted their own food.

The book has two authors, which accounts for some of the gaps and disjunctions in its construction. The primary author, whose name is in larger font on the cover, is Andrea L. Smalley, an emerita professor of history at Northern Illinois University. Under her name, in smaller typeface, it reads “with Henry M. Reeves.” Reeves was a wildlife biologist who worked for the US Fish and Wildlife Service for several decades, retiring in 1983. He compiled boxes and boxes of source material and notes on “the market in birds”—the apparently insatiable craze for wild birds as game for urban restaurant menus, as feathers for ladies’ hats, or as specimens for gentlemen’s collections. Reeves never managed to bring the material together as the book he envisioned, and after his death, Smalley took up the project, endeavoring to organize the material along a narrative arc, and with an historian’s eye.

The result is uneven, and bears the marks of its assembly. The book makes the claim that the wild bird market was distinct from previous extractive markets in wild animals and their parts. It mentions the long-standing trade in beaver pelts, exported to Europe for hats, and the near extermination of the buffalo. The authors maintain that fur trappers and deerskin hunters, “although hunting for the market […] were not market hunters in late nineteenth century terms.” This struck me as a distinction without a difference, and that remained a frustrating theme throughout the book.

Reeves’ enthusiasm for the subject is evident in the deep dive he clearly took into primary source material. He includes colorful passages from newspaper articles, game dealer trade publications, and especially essays and letters to the editor in Forest and Stream magazine. Unfortunately, these are rarely contextualized into a larger thesis, or critically analyzed. They are mostly presented credulously, without much commentary. We are, it seems, just supposed to take these “sportsmen” as reliable narrators of their own motives. Without an authorial stance to give us some sense of how to understand these writers, reading this book sometimes feels like sitting at a microfiche machine in a library basement, reading issue after issue of these old periodicals, and having no one to help you interpret them.

What constitutes a sportsman was slippery at the turn of the century, as it continues to be now. The book’s main theme is the debate about the division between “market gunners” and “sport hunters,” and I finished the book still unclear on what that difference really was, and, astonishingly, also unclear on what the authors think the difference was. Sportsmen made a lot of vague claims about their ethics and values around wildness, but many sport hunters were just as wanton in their killing as any hunter shooting for maximum profit. They posited their respect for nature, and their deeper understanding of it, but a successful hunter-for-profit had to possess a naturalist’s awareness of wild birds’ seasonal rhythms and habits. Hunters for the market weren’t immune to the joys and rewards of being deep in the wild either, but sportsmen derided them and waxed poetic about themselves, as if only they had the proper sensibilities for it.

The book’s failure to give any coherent assessment on the difference between a “sportsman” and a “market hunter” seems to be down to its deepest failing overall: a near complete lack of awareness of class, ethnic, and racial hierarchies at the heart of the entire debate. “Sportsmen” were chronically dog whistling about class and ethnicity, sometimes subtly, other times more overtly, though the book rarely engages with this. A passing reference to it comes up almost 200 pages in with: “Under the title ‘To Whom Will You Entrust the Making of Our Game Laws?’ the Western Wildlife Call paired the names of sympathetic, safely Anglo-American state legislators with a list of mostly Italian commercial dealers and market shooters.”

The book similarly stumbles on matters of gender. The authors include multiple quotations from newspapers and magazines reflecting the unsurprising and casual misogyny of the time; birds, wrote William T. Hornaday, needed to be made “secure from further attacks by the bloody-handed agents of the vain women who still insist upon wearing the wings and feathers of wild birds.” Men, to be sure, were no less status-obsessed. But the book fails to note the parallel vanities while describing the gentlemen who prowled markets for the rarest, most endangered eggs, plumes, and taxidermied mounts to display in their curiosity cabinets, or the captains of industry who demanded their tables be strewn with woodcock, pintail, and snipe to impress their colleagues and competitors. More egregious than this failure of comparison, though, is the complete omission of the women who championed the social and legislative shifts that led, ultimately, to the Migratory Bird Treaty Act. The founders of Mass Audubon, Minna Hall and Harriet Hemenway, as a stark example, are never mentioned in the book. They are, I presume, obliquely alluded to with the phrase, “the revitalized, female-led Audubon movement.” It’s a bizarre exclusion that feels almost purposeful, given how many male conservation leaders are specifically name-checked and given plenty of ink.

Ultimately, the book is an intriguing walk through a curious chapter in American history, when it was dawning on at least some people that humans could now drive massive, landscape-scale exterminations, like that of the passenger pigeon. There are intimations in the book of what that might have felt like to those watching the mournful history unfold, and I find myself wondering about their experience of it, especially as we modern Americans grasp and grieve the scope of our capacity to alter the global climate. Among the many missing voices in this book, I’d like most to be able hear those ordinary ones, caught up in currents stronger than they were, in a nation, as the author concludes, “consumed by capitalism.”

Sarah Courchesne

Program Ornithologist

Mass Audubon North Shore

Joppa Flats Education Center

Header photo: Pelican Island National Wildlife Refuge, USFWS

Suggested citation:

Courchesne, S. Review of the book The Market in Birds: Commercial Hunting, Conservation, and the Origins of Wildlife Consumerism 1850-1920. https://afonet.org/2023/05/the-market-in-birds/.

If you are interested in contributing a book review, or if there is a book you would like to see reviewed on our site, you can contact our Book Review Editor, Evan Jackson at evan.jackson@maine.edu