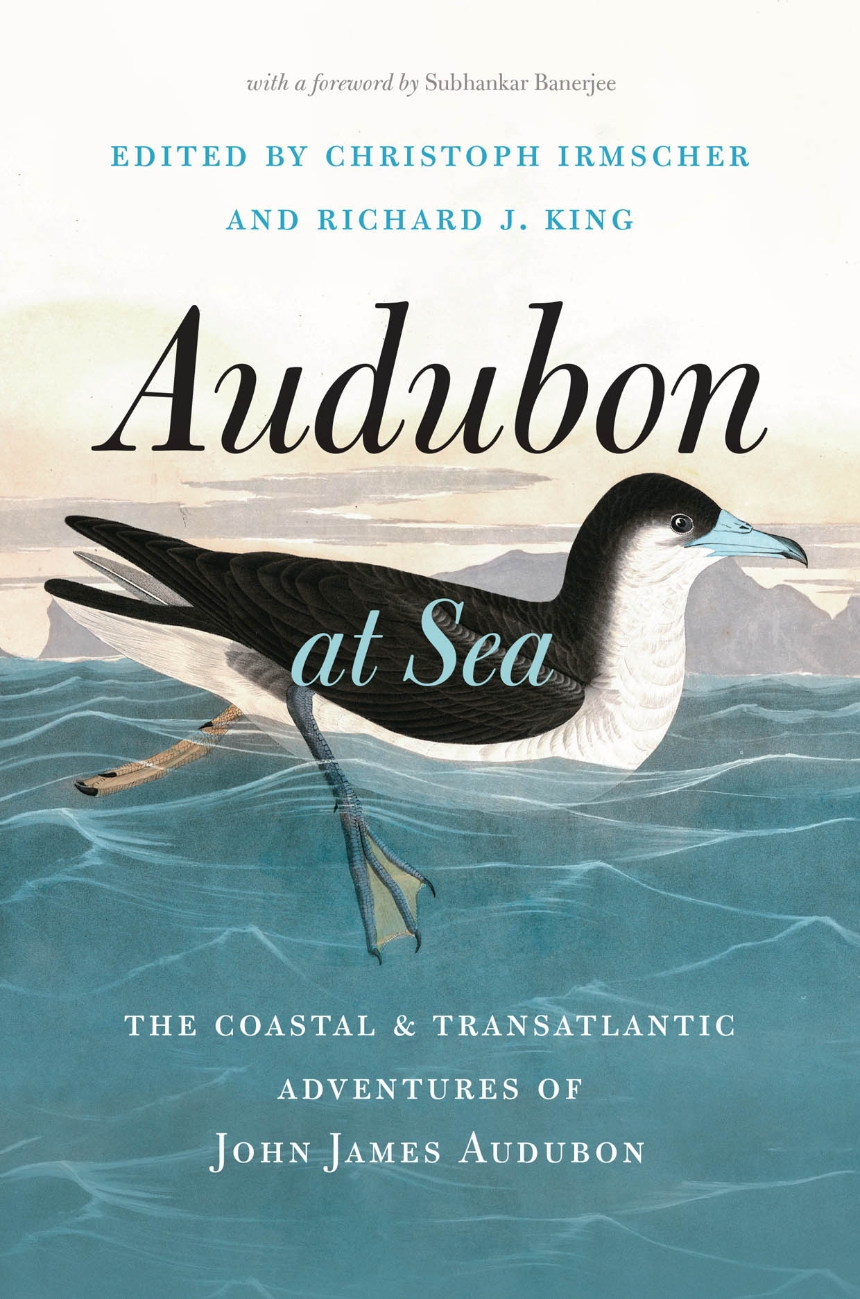

Audubon at Sea: The Coastal and Transatlantic Adventures of John James Audubon. Christoph Irmscher and Richard J. King (eds.) with foreword by Subhankar Banerjee. 2022. The University of Chicago Press. Chicago and London. 352 pages.ISBN-13:978-0-226-75667-7. Hard cover ($30)

Christopher Irmscher (a noted Audubon Scholar) and Richard J. King ( an accomplished writer about marine literature) provide an excellent review of John James Audubon’s waterbird adventures at a time of renewed interest in Audubon’s place in ornithology history and recent controversy about his life as a slave owner during this time of racial awakening.

Audubon is best known for his art and discoveries of landbirds. His focus on land birds in the early years of his bird art was in part because he abhorred boats and held an acute terror of becoming seasick. Yet in his quest to illustrate all of the birds in North America, he could not avoid seabirds and this forced him onto ships where he was very uncomfortable and a reluctant traveler. Audubon wrote: “ A long voyage would always be to me a continued source of suffering, made tolerable from gazing on the vast expanse of the waters and on the ever-pleasing inhabitants of the air that now and then appear in the ship’s wake.” Always eager to return to firm footing on land, he wrote: “Let the wind blow high or not, I care little which, provided it waft me toward the shores of America.”

Audubon at Sea includes Audubon’s journal from his 1826 voyage to England, coastal essays from the years 1831 to 1839) and accounts from his 1833 voyage to Labrador. The book includes 20 color plates of Audubon paintings from the Elephant Portfolio edition and 38 halftones by Audubon and others that illustrate the boats and people encountered on his voyages with detailed footnotes from the editors.

Part I of Audubon at Sea includes excepts from Audubon’s 1826 Journal aboard the Delos that is transcribed directly from the original manuscript. The authors preserve Audubon’s inconsistent punctuation and spelling and hold that his erratic capitalizations and misspellings are a feature of his style that became greatly improved as he eventually developed a gift for lyrical prose.

Audubon at Sea provides new insight into three overlooked but important aspects of Audubon’s legacy. First, readers will see how his waterbird writing evolved from imperfect to polished and became highly readable. Audubon is best known for his art, but his later lyrical prose beautifully complements his art. Second, Audubon at Sea shines new light on Audubon’s descriptions of seabird habitat and through this book, his waterbird art receives new attention even though most waterbirds live in places that few visit. This is increasingly important since many seabird populations are declining from human-caused assaults. This book is a significant overview of Audubon’s legacy as a great artist, writer, and adventurer.

Part II, the bulk of the book, is a collection of essays about waterbirds from a variety of habitats, including many coastal habitats. These essays include much more than seabird topics. Here are Audubon’s encounters with flamingos, plovers, and shorebirds along with his adventures with pirates and other ne’er do wells which he encountered while pursuing birds for his art.

Part III includes Audubon’s 1833 collecting voyage from Eastport, Maine to Labrador aboard the Ripley. The original manuscript journal from this voyage is lost, so the editors relied on Lucy Audubon’s “The Life of John James Audubon the Naturalist (1869) which contains extensive editing of his original journal by Lucy Audubon and others. Audubon explored the Labrador coast at a time of great seabird abundance, so his descriptions of the vast numbers of seabirds and the massacre of their numbers by himself and his fellow travelers and commercial hunters gives a sense for the abundance at the time. Although he fully participated in the massacre of thousands of murres, this trip shows the beginning of his conservation awareness when he observed that: “if humans didn’t stop what they were doing there, soon all the “fish and game, and birds” would be gone and nature would be “left alone like an old worn-out field.”

Audubon’s journals graphically show how he would kill birds for specimens, even those that he suspected were becoming rare. For example, Eskimo Curlews, were still plentiful during his Labrador expedition, but his writing reveals that he could foresee their dire future- yet he still shot seven and somehow couldn’t draw them properly. His “Esquimax curlew” shows a male bird perched above its prostate, dead mate. The editors suggest that perhaps he could see the future of the species. His encounter with a magnificent frigatebird illustrates his sense of wonder, his observation skills, and his adeptness with a rifle. Audubon wrote: “The Frigate Pelican is possessed of a power of flight which I conceive superior to that of perhaps any other bird. However swiftly the Cayenne Tern, the smaller gulls, or the jaeger move on wing, it seems a matter of mere sport to it to overtake any of them.” To satisfy his curiosity, he tells the story of how he observed a bird scratch its head with its feet, drop in elevation, and come within his shooting range. On closer inspection, he could see the comb-like toe adaptations were jammed with insects collected from the frigatebird’s head.

Audubon at Sea provides new insight into three overlooked but important aspects of Audubon’s legacy. First, readers will see how his waterbird writing evolved from imperfect to polished and became highly readable. Audubon is best known for his art, but his later lyrical prose beautifully complements his art. Second, Audubon at Sea shines new light on Audubon’s descriptions of seabird habitat and through this book, his waterbird art receives new attention even though most waterbirds live in places that few visit. This is increasingly important since many seabird populations are declining from human-caused assaults. This book is a significant overview of Audubon’s legacy as a great artist, writer, and adventurer.

Stephen W. Kress

Founder, Project Puffin

Visiting Fellow, Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology

Literature Cited:

- Audubon, L. 1869. The Life of John James Audubon the Naturalist. G.P. Putnam and Sons.

Header photo: Common murres (Uria aalge) Lisa Hupp/USFWS

Suggested citation:

Kress, S.W. A review of the book Audubon at Sea: The Coastal and Transatlantic Adventures of John James Audubon. Christoph Irmscher and Richard J. King (eds.) with foreword by Subhankar Banerjee. Association of Field Ornithologists Book Review. https://afonet.org/2023/07/audubon-at-sea-the-coastal-and-transatlantic-adventures-of-john-james-audubon/

If you are interested in contributing a book review, or if there is a book you would like to see reviewed on our site, you can contact our Book Review Editor, Evan Jackson at evan.jackson@maine.edu

One thought on “Audubon at Sea: The Coastal and Transatlantic Adventures of John James Audubon”

Comments are closed.