I never imagined that a simple Instagram post would ignite the spark for my Master’s thesis research. But in 2021, that’s exactly what happened. While scrolling, I came across a photo shared by the National Audubon Society. It showed a man spreading bright orange goop on a rock, with a caption explaining that this unusual tactic was being used to reduce predation on ground-nesting shorebirds in New Zealand.

At the time, I was working as a seasonal shorebird technician for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in southern Rhode Island. Every day, I witnessed just how hard it was for species like Piping Plovers to successfully fledge chicks. The odds were stacked against them. Human activity on crowded beaches, off-leash dogs, and shrinking nesting habitat made it hard enough. But the real heartbreak was predation. Coyotes, skunks, opossums, red foxes, and fish crows were relentless. Too many times, I’d check on a nest that was just days from hatching, only to find shattered eggshells and paw prints in the sand. It was frustrating, to say the least.

The image of that orange goop stuck with me. What if this approach could work on our beaches too? With that thought in mind, I reached out to my supervisor, and together, we connected with the researchers behind the goop in New Zealand. Those conversations sparked an idea: why not test it here in Rhode Island?

The Research

The basic premise of my research was modeled after what researchers were doing in New Zealand: testing a non-lethal method to deter mammalian predators from preying on shorebird eggs. The approach aimed to “condition” mammalian predators by exposing them to chemically-extracted bird scent applied throughout shorebird nesting habitats. The goal was to habituate egg-eating predators to the presence of bird scents without any food reward. By breaking the association between bird scent and food, the method sought to reduce predator interest in actual bird nests.

Researchers in New Zealand found this method to be highly effective at reducing nest predation overall. However, the New Zealand study was conducted in a different habitat, with different nesting shorebird species, and different mammalian predators. This presented an opportunity to test the method on Rhode Island’s coastal beaches, where the ecosystem dynamics differ significantly from New Zealand’s.

Lab and Fieldwork

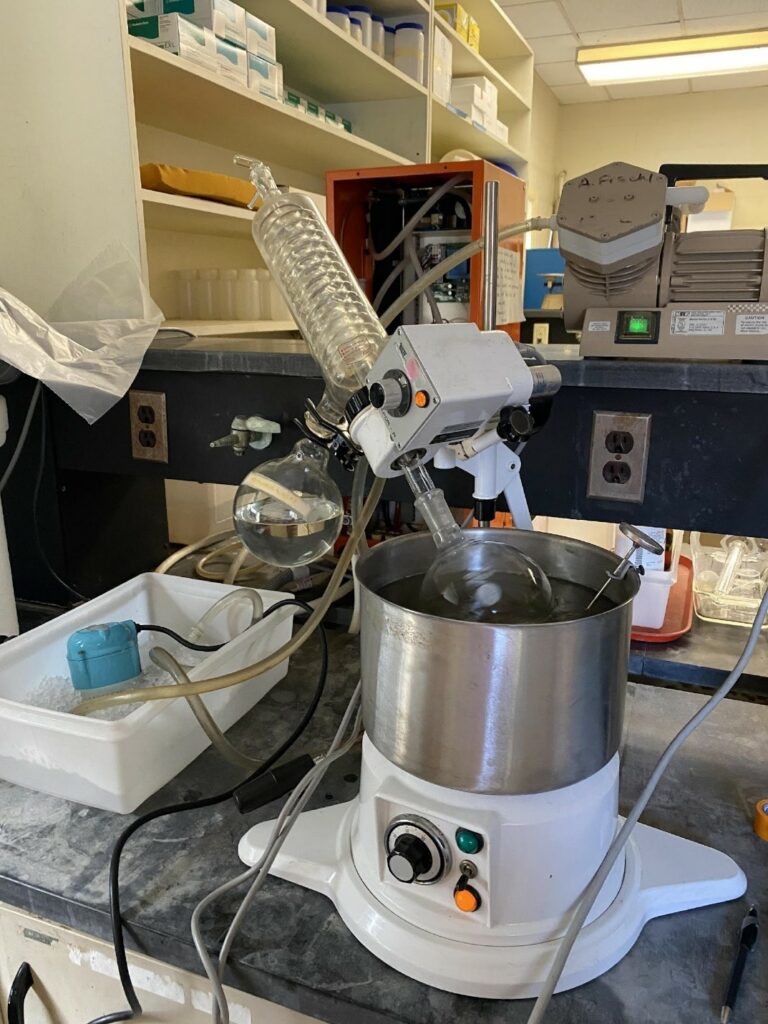

A major obstacle at the beginning of this project was creating the bird odor. I’m no chemist, and trying to figure out how to use a rotary evaporator with only the knowledge of a General Chemistry class from over a decade ago made things… difficult.

So, I reached out to the chemist who originated this method in New Zealand, and with their guidance, I was able to create bird odors for my project. The scents I made were from bird species that were local to the Rhode Island beaches where I was testing this method. These included Black-backed Gulls, Herring Gulls, Ring-billed Gulls, Mallards, Mergansers, Geese, Brandt, and more. The scents were derived from a mixture of gull and waterfowl carcasses, as well as directly from the uropygial glands (preening glands) of waterfowl.

Fieldwork took place on two beaches in southern Rhode Island: Trustom Pond National Wildlife Refuge and Ninigret National Wildlife Refuge. These long, linear beaches provided ideal testing grounds for the method. We set up 33 scent stations at Trustom and 48 at Ninigret. Each “scent station” consisted of a trail camera and a rock placed 10 feet in front of the camera. With a gloved hand, I would spread the bird goop onto the rock. The trail camera then captured any animals that came to investigate the scent. Scent types were randomly switched and applied every three days to ensure scent coverage across the landscape.

The main visitors to the scent stations were coyotes, red foxes, skunks, and opossums. We also saw bobcats, domestic dogs, deer, rabbits, and mice investigating the scents. The most notable interactions were coyotes and red foxes scent-marking the rocks. In some cases, coyotes were even seen rolling in the scent — an instinctual behavior observed in canids.

Did It Work?

The goal was to “trick” predators into thinking bird scents weren’t worth investigating. The results were mixed. The smell of waterfowl glands was particularly interesting to predators, as they’d spend considerable time sniffing around and investigating. Scents derived from preening glands piqued the most interest, with mammals lingering the longest around those scents. Coyotes, in particular, seemed to learn over time that certain smells weren’t worth investigating.

However, not all predators “gave up.” Some persisted, continuing to investigate and interact with the scent stations. Unfortunately, the scent treatment did not stop predators from finding and eating Piping Plover eggs. While some predators appeared to lose interest in the scents over time, others remained persistent in their search for food.

A Dream Fulfilled

In the world of wildlife research, landing a fully funded project is no small feat. Positions like these are fiercely competitive, and getting an interview for a graduate position can feel like a long shot. But somehow, I found myself in a position I never expected — bringing a fully funded research project to the table. And not just to any table. I was pitching it to a professor I had admired for years, one I’d dreamed of working with.

This journey taught me something important: inspiration can come from the most unexpected places. All it takes is a little curiosity, a lot of persistence, and the courage to chase an idea that just might work. For me, it all started with an Instagram post — and it turned into something so much bigger.

Although the results weren’t what I had hoped for (reducing predation on Piping Plover nests), this project taught me that science is not always about perfectly controlled experiments and clear outcomes. Sometimes, it’s about being willing to try something new, learning from it, and figuring out what to do next.

Nicole D. DeFelice

Department of Natural Resources Science

University of Rhode Island

The results of this study were recently published in the Journal of Field Ornithology:

DeFelice, N. D., M. M. Durkin, P. Paton, and B. D. Gerber. 2024. Odor swamping did not deter mammalian predators from depredating shorebird nests on beaches. Journal of Field Ornithology 95(4):6. https://doi.org/10.5751/JFO-00557-950406.

Header photo: Piping Plover (Charadrius melodus) by Harry Collins | Getty Images.