With all of the incredible revelations in ornithology during the 21st century, it’s easy for a young birder who wants to “discover new things about birds” to feel like they’re late to the scene. But upon getting deeper into field ornithology, it becomes readily apparent how much basic life history of North American birds remains poorly known. For people who are interested in the intricate details of bird’s lives, even for common backyard birds, there are still ample questions for a budding ornithologist to ask, and better tools than ever to answer them.

In this project, we made use of readily available information collected by tens of thousands of people across North America who devoted long hours to checking mist nets, scanning the skies at bird observatories, walking the streets to pick up window collision victims, counting their backyard feeders, stopping and going along their breeding bird survey routes, and entering eBird checklists on their birding outings. Without the decades of work gathering this information and the recent efforts to make it publicly available online, it would have been impossible for us to have access to hundreds of thousands of nuthatch observations across a broad geographic region. But because we had it all at our fingertips, we were able to investigate natural history reports in a rigorous, detailed way scarcely imaginable to prior generations.

Observers at Cape May, Hawk Mountain and other visible migration watch sites in the Northeast have known for decades that White-breasted Nuthatches fly in with irruptive boreal species in “irruption years”. Spectacular historic counts at Bake Oven Knob in Pennsylvania, Long Point in Ontario, and Derby Hill in New York made it clear that at least in certain years and certain places there were mass movements of this species. However, the breadth and regularity of more normal levels of irruption mostly stayed under the radar of the ornithological research community, probably because the migrant arrivals blended in with healthy resident populations of White-breasted Nuthatches.

After notable movements of White-breasted Nuthatches in fall of 2018 that were reported on social media, our group became fascinated by the idea of this cryptic migration. We began to look at other data sets, and the more we dug the more we found.

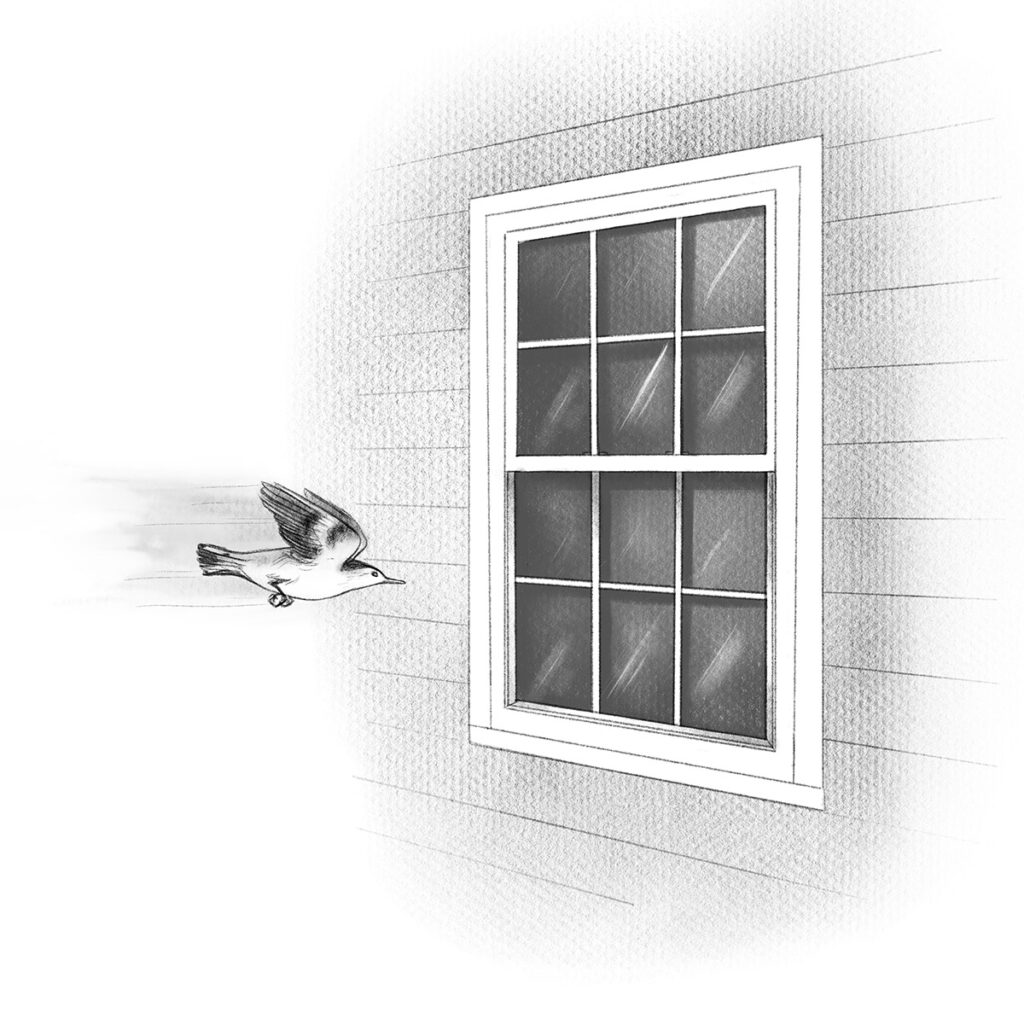

Bird observatory data were key to showing the two-year irruptive pattern in eastern White-breasted Nuthatches. Daily monitoring at Long Point, Ontario, showed fall peaks averaging 51 birds during high movement years, while the peak in low years was only 3 birds. Hawk Mountain Sanctuary, Pennsylvania, recorded fewer total birds in flight years than at Long Point, although with similar peak passage in October, and annual fluctuations were strongly correlated between these sites. Peak numbers at Cape May Bird Observatory in New Jersey were lower yet and delayed to the end of October as expected for a more southern location. A database of window collisions from Toronto showed an order of magnitude more dead White-breasted Nuthatches found in the city during the irruption years when Long Point was banding them in big numbers compared to the non-irruption years.

Large-scale community science datasets were instrumental in demonstrating this species’ movements on larger geographic scales. Instead of counting individual sightings, we looked at the percentage of checklists reporting nuthatches in three databases: Project FeederWatch, eBird, and the Study of Bird Populations in Quebec (ÉPOQ). It was clear that observation rates in the northeastern United States increased in the fall of irruption years and stayed elevated through the next spring. In central and southeastern regions of the United States, nuthatches were observed at nearly the same rate irrespective of whether it was an irruption year or not further north, indicating that facultative migrants don’t reach these areas in substantial numbers.

We even found evidence of irruption in the total numbers of White-breasted Nuthatches banded across northeastern North America. More birds were banded during fall irruptions than in other years. Tellingly, adults were captured during irruptions in places where the species normally does not breed, showing that adults as well as young of this “normally resident” species take part in the movements.

In our search for factors that influence White-breasted Nuthatch irruptions, we found an excellent resource in the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Their database on mast productions of a large variety of trees and plants showed a two-year trend for fruit and seed abundance. High production levels in one year consistently coincided with low numbers of nuthatches on the move, whereas poor production years matched up with high nuthatch abundance at migration count sites. The connection was strengthened by the fact that two sequential high mast years in 2010 and 2011 coincided with two consecutive years of low nuthatch numbers.

We hope that our work brings attention to the utility of community science datasets for addressing longstanding natural history topics, and that our findings inspire other researchers to take similarly integrative approaches to investigating the populations and behavior of familiar birds. In particular, irregular and partial migrants provide unique opportunities to study the costs and benefits of movement in the face of variable environmental conditions. As many scholars have noted, migration is not simply a binary trait where whole species can be neatly sorted into “migratory” and “non-migratory”, but rather there is a flexible continuum of dispersal and migrant behavior that varies between subpopulations and between individuals. We believe that the methods that we used in this paper provide a template for more such work to investigate the causes of occasional movement in other largely resident species. We encourage all community science members, from budding beginners to seasoned veterans, to continue submitting their observations of these “backyard” species. Collectively, this knowledge is a driving force for new insights and discoveries about avian migration.

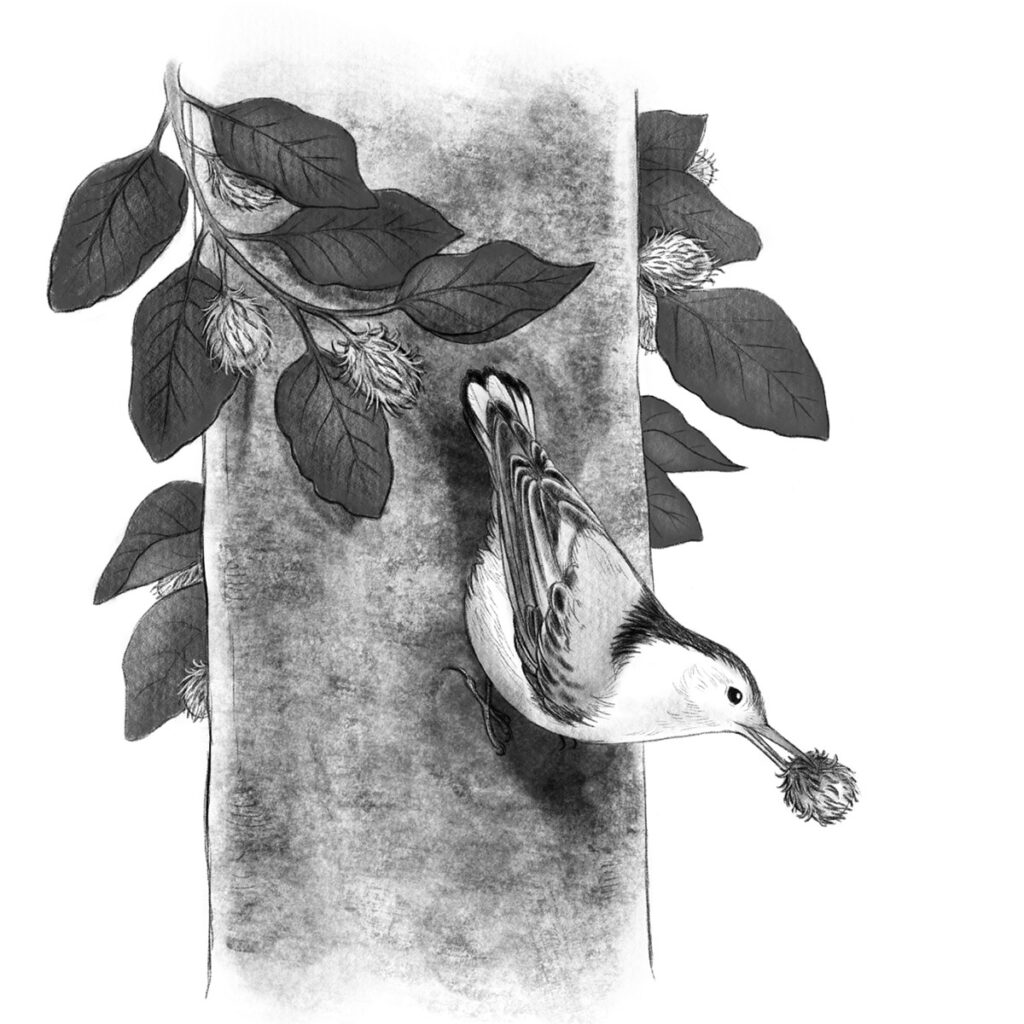

1.) In non-irruption years, mast crops tend to be high, and White-breasted Nuthatches tend to be more sedentary. 2.) Irruptions appear to be triggered by an absence of mast, and many White-breasted Nuthatches are theorized to depart from their breeding territories. 3.) In these low mast years, more adult and immature White-breasted Nuthatches than normal are detected at banding stations, especially at Long Point Bird Observatory. 4.) Higher numbers are also found dead from window collisions in Toronto during the fall migration period of these irruption years. 5.) A higher percentage of bird feeders in the northeastern US report White-breasted Nuthatches in the winters after the fall irruption than the non-irruption winters. Illustrations by Nicole Dornsife.

The results of this study were recently published in the Journal of Field Ornithology:

Dunn, E., A. Dreelin, P. Heveran, L. Goodrich, D. Potter, A. Florea, B. Ewald, and J. Gyekis. 2022. Community science reveals biennial irruptive migration in the White-breasted Nuthatch (Sitta carolinensis). Journal of Field Ornithology 93(2):2. [online] URL: https://journal.afonet.org/vol93/iss2/art2/

Guest blog post by:

Joe Gyekis

Pennsylvania State University

Paul Heveran

DeSales University

Ricky Dunn

Long Point Bird Observatory

Andrew Dreelin

Northern Illinois University

Andra Florea

Université du Québec

Laurie Goodrich

Hawk Mountain Sanctuary