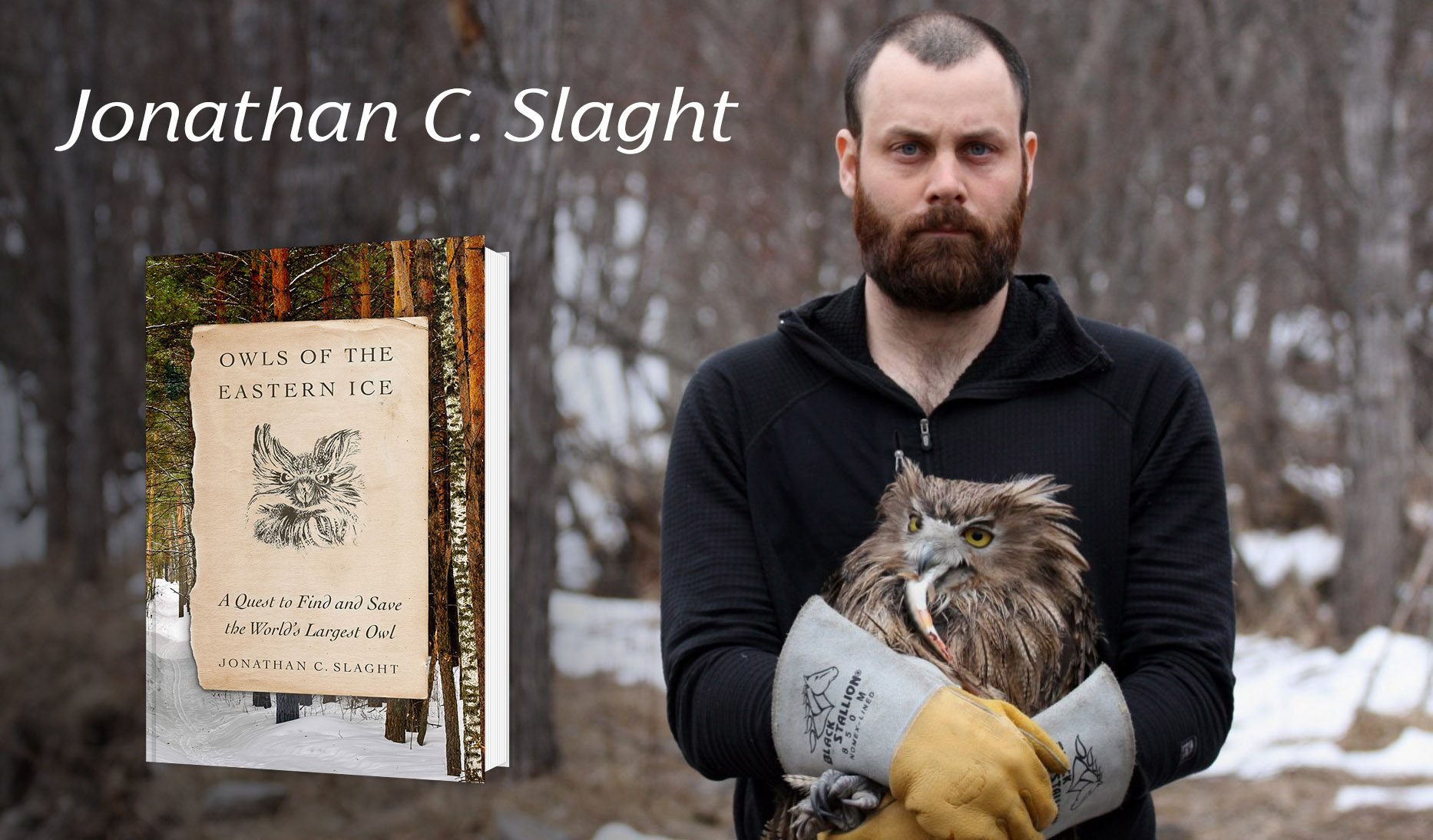

While arranging the review of Owls of Eastern Ice, I had the pleasure of interviewing the author, Jonathan Slaght. Our conversation is below.

Ashworth

For those not familiar with Owls of the Eastern Ice, can you share sort of a Reader’s Digest condensed version of your book and the research that went into it?

Slaght

Sure. It’s essentially a play by play of my Ph.D. research at the University of Minnesota. It starts with the process of conceiving a study, designing a study, collecting the data, analyzing the data, and coming up with conservation recommendations. That’s sort of the play book for anyone’s Ph.D., right? So, I think what the book really gets into is the significant trials and tribulations of converting a plan on paper to the realities of the field…of field work. This story…the research took place in a relatively remote and exotic place compared to a lot of US based research. We had to deal with a number of not just standard problems that come up but weather conditions, so we had to adjust our methodology, things like blizzards and floods. Just the realities of living and trying to work in a remote landscape with an endangered species. This owl, the Blakiston’s Fish Owl, which does not like to be found or even looked at by humans. So, the idea behind it was to catch some birds, put on tags. At first it was VHS transmitters. The owls immediately ripped those antennas off so that did not last more than a season. Then putting on GPS tags to track their movements and then develop a conservation plan based on those movements.

Ashworth

Obviously, I read the book and I thoroughly enjoyed it but there was the horrible storm at the end. Can you catch us up? What has happened since that terrible storm at the end of the book?

Slaght

So, the storm…this was a typhoon. It’s what they call hurricanes in the Pacific. They’re typhoons. Just like in North America, there’s a storm season. There’s a typhoon season. The typhoons are going to come through and they are going to go up the coast of the western side of the Sea of Japan in Russia, where this story took place, on a semi-regular basis. It’s just that this one was one of these “mother of all storms”. It came in and settled over some really prime fish owl habitat. There’s a reserve there. There’s this 4,000 square kilometer reserve called the Sikhote-Alin Reserve that is great fish owl habitat. There are big, old growth trees that they can nest in and some salmon-rich rivers. Forty percent of the tree cover in that reserve was flattened by these gale force winds. So there have been a dozen fish owl territories I’ve been monitoring with my Russian colleagues for more than a decade. We went to visit one of these sites after the storm to see how they weathered it and the forest was gone. The entire old-growth patch was a gravel bar because the river had jumped its bank and the flooding, like a saw, cut through this patch of forest, washed it all out to the Sea of Japan, and there was nothing left. It’s 200 to 300 years for trees to come back of that same size. So, that’s a challenge. People like us can do…there are a lot of mitigations that we can do to help endangered species either recover or maintain habitat, but things like climate change, what can we do? Just like in North America, the intensity of these storms and the frequency of these storms is increasing. That’s going to continue to be detrimental to fish owls and their habitat.

Ashworth

You’re kind of modest. You’ve described how you put your Ph.D. methodologies together and went and did this, but can you describe how harsh that environment is? What was the lowest temperatures that you and your team encountered?

Slaght

It was certainly in the mid minus 30’s. That’s for sure. I’m sure it got colder than that. Often when it was colder than that I wasn’t really paying attention to exactly how cold it was. We were living sometimes in tents. That was I think the most unpleasant. More often than not we were living in the back of this Soviet-era transport vehicle. This truck that had this custom-built…essentially a two-bedroom apartment built on the back with a wood stove. It was pretty nice. We would go to sleep wearing t-shirts because it was so warm from that wood stove but by morning the cold would just find its way in and there would be things stuck to the walls from the ice. And there were issues. We carried these car batteries everywhere that we would go and those things would drain very quickly in the cold. We had trap sites for the owls and a blind nearby…and cameras and cables. The cables would snap like twigs when it would get that cold. You would step on one inadvertently as it’s next to the trail between the blind and the capture site. It was weeks at a time. Up to six weeks at a time. Just being out there. Going into town…town being villages of a couple hundred people, 1 to 3 stores every few weeks to get some basic supplies. Yeah, it was remote.

Ashworth

Where does Blakiston’s Fish Owl research go from here? What do you see as the future for it?

Slaght

That’s a good question. There are a couple of ideas that my Russian colleagues and I are trying to focus on. One, we have not done another telemetry study. The people that I describe in the book, the people that I worked with then, I am still working with them now on fish owls. We are consistently doing something every year and have done since 2006. We have not captured birds since 2010 sort of when the book ends because there hasn’t been a solid reason for us to. These birds are endangered species and not just that…going through the process of catching something, putting a tag on it, and then forcing it to carry this burden for a year or however long the tag is on is not that great for the bird. So, we’re not interested in doing things just for the sake of doing things, but we are starting to realize that to better understand how the species uses the landscape and how to better manage that landscape…we need to better understand juvenile dispersal. We have these young birds, once they fledge, they typically stay on their natal territory for at least year and a half learning how to be a fish-eating owl in a place where most waterways freeze for months on end. So, they stick around for a long time on their natal territories before dispersing. The question is: What are they doing? Where are they going? How are they using that habitat? We have a really good sense of what nesting habitat is…what a core of a fish owl’s territory looks like, but I think we need to better understand juvenile dispersal and juvenile habitat use. There is a second avenue of research. There are between 1000 and 2000 individuals in the global population. Most of those are on the mainland, the Russian mainland, almost certainly some in China, we really have no idea how many, probably not very many, and there are about 200 of them on the Japanese island of Hokkaido and the southern Kuril Islands in Russia. They used to be on this island called Sakhalin, which is just north of Japan. They were certainly there in the 1970s. There haven’t been any confirmed sightings since the 70s. The question is Why? What we’d like to do, given that the island subspecies is so endangered, there are about 200…which it is actually a really good conservation success because that’s double what that population was in the early 80s. So next year we are interested in doing a survey of Sakhalin Island trying to get a sense of if there are fish owls there and if they’re not there, try to figure out why and also try to identify good habitat to potentially do some reintroductions from the islands to give those island birds a little more room to breathe.

Ashworth

When I was younger, I was in the USMC, and I’ve always loved adventure literature so the entire time that I was reading your book I was rooting for you and Sergey and the whole team. I’m also cheering for the owls. It’s very easy to get wrapped up in that book. As a reader, you become part of the book in a way…that’s kind of my experience. The whole time, I’m also thinking about other things that I’ve read. I’m thinking about Hemingway, Ruark, and Capstick, and all this adventure literature. When you talked about the two-bedroom apartment, I started thinking about Steinbeck and Travels with Charley. How he drove around the country. I think with the way our culture is nowadays, when someone says “research” a lot of our fellow Americans see these folks in white lab coats with pocket protectors and they think ‘how boring’. Do you think that there’s a way to take your research, your book, and the works of others, and market research differently? Maybe there are some adventurous folks out there that don’t want to go join the Marines or the French Foreign Legion but they want some adventure in their life. Do you think there is a way that we can repackage this? Not only as ornithologists, herpetologists, botanists, there’s really a big realm…. Maybe we can reshape this in a way?

Slaght

Yeah, that’s interesting. A few things. I think my favorite feedback I get from the book is reviews that say ‘this doesn’t sound interesting, but…’ or ‘I had no idea how much work goes into this.’ I think that’s an important take way for us and for our field, right? A lot of people don’t get it and this book is helping them get it. It’s not just hippies putting fences around things and not letting us cut down trees. It’s a job. It’s work. We don’t just come up with these conservation recommendations. It’s backed by years of sometimes very difficult and unpleasant research. I try to make this point in the book. Some people do view this type of work as vacation. You know, ‘they’re just off having fun in the woods.’ Well, it’s not always fun. It can be very cold. It can be very unpleasant, and it can be really boring. So much of science is having a protocol and following that protocol again and again and again and again to collect your data. So, I do think this book does help open some eyes to the fact that this stuff is interesting, but I want to have that caveat that yes, there is a lot of excitement and adventure but there’s a lot of stuff that you need to do that will be unpleasant. I talk to a lot of graduate students and undergraduate students and you just see their eyes light up….tigers, musk deer, wild boar, fish owls and they are like “Yes. Yes. Yes. I want to do that” AND freezing in a tent and falling through the ice and all this other stuff. I want to paint a balanced picture so that people don’t get into this deal thinking it is all sunshine and endangered species and beautiful vistas. I want to sort of ground people as well.

Ashworth

Is there anything that folks who read this interview can do to help Blakiston’s Fish Owls?

Slaght

You know, I’ve given close to a hundred talks in the last year and a half since the book came out and for some reason, I still don’t have a great answer to that question. On a fundamental level, and a lot of people will tell you this, looking at where natural resources come from right? I make this point at the end of the book that timber from Primorye’s forests, trees from fish owl habitat ends up in North America, it ends up in Europe. The fish, the same species that the fish owls are hunting, are commercially harvested and are sold throughout Asia. So, it’s important that these natural resources are sustainably harvested as much as they possibly can be. So, paying attention to sustainability certifications, paying attention to which species are being harvested, and how they are being harvested. That really does matter to fish owls even though we are here in North America making these decisions.

Ashworth

Anything else you want to tell readers about fish owls?

Slaght

I think they are neat birds. I’m just absolutely thrilled that a book that I thought would only have a niche audience has been so well received. People who wouldn’t know about or care about fish owls know and care about fish owls. I think a big part of conservation is public awareness. The more people that care about the birds I think they are less likely to go extinct and be in trouble. That’s a big plus!

Darrell Ashworth

AFO’s Book Reviews Editor

Header photo by Takashi Yanagisawa via Pixabay