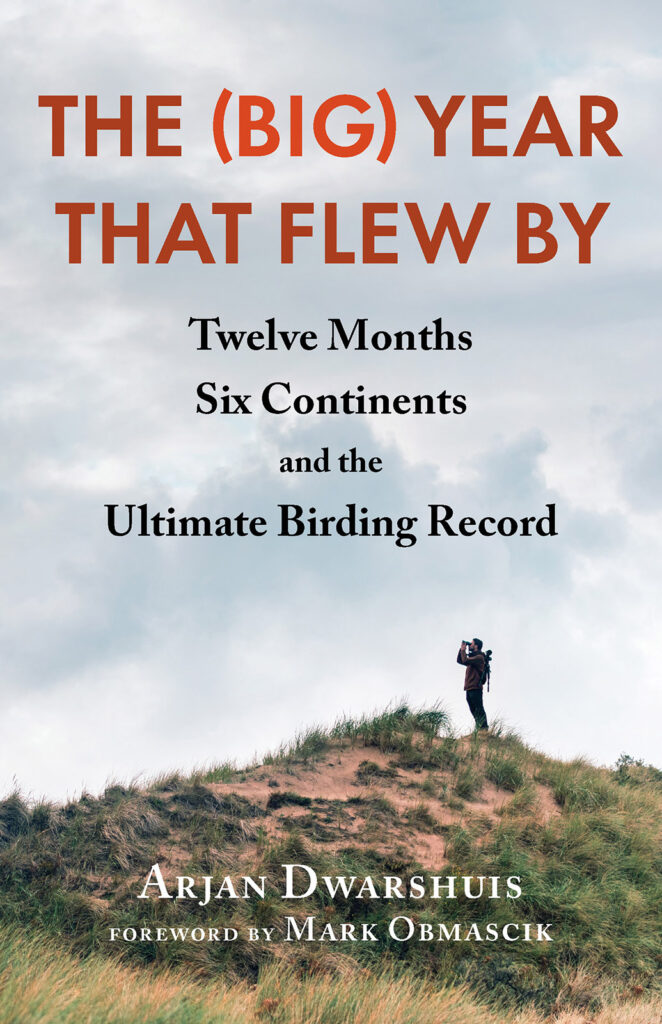

The (Big) Year that Flew By: Twelve Months, Six Continents, and the Ultimate Birding Record. Arjan Dwarshuis. 2023. Chelsea Green Publishing, White River Junction, VT, USA and London, UK. 256 pages. ISBN 9781645021919. Paperback ($22.95 USD).

It’s a given that birders like to keep lists. We all, to a greater or lesser extent, do it. Whether it’s a world list, a state or county list, a house or garden list, a self-found list, or even the more esoteric stuff like a commuting-to-work list – we seem to gravitate towards them, for better or worse. At their best, lists form part of an ongoing data gathering exercise that feeds information to a local or national body who can use that data to plot trends in bird population or distribution, providing granular detail that helps to form a useful bigger picture. Your daily birding walk, if it generates a list that’s uploaded to eBird, is contributing to something larger than merely satisfying your desire to perhaps find a new bird for your local patch list.

And then there are year lists. What of them? Twelve months in which an individual tries to see as many species as possible within a self-defined geographic boundary. If we’re trying to justify keeping lists, there’s an inherent sense that this is a harder proposition to sell. A year list, or a so-called big year, is ultimately all about the individual. Who, apart from oneself, really cares if one has seen x species in the space of a year?

Which isn’t to say it’s not a lot of fun. I should know – in 1995, when I was a little younger than Arjan Dwarshuis, the author of The (Big) Year That Flew By, I set out to do a British year list. I had a great time, saw some exciting vagrant birds, and met some interesting people, but I forget the exact total I ended the year on – somewhere a little north of 350 species I think, which for Britain is good going. But my vagueness about the final score perhaps tells me something – the effort was more about the experience itself than anything profoundly meaningful.

Indeed, by the end of the year I remember a feeling of hollowness that pervaded my birding. I was spending a lot of time and money (and, though we didn’t think of the implications at the time, burning a lot of fossil fuel) chasing birds simply to add a number to a list. I didn’t like to admit it to myself, let alone my peers, but the whole pursuit of a record-breaking total of birds had come to feel like a fairly pointless undertaking.

All of which serves as some context to Arjan’s record-breaking big year in 2016, a year in which he ended up travelling the world and seeing over 6,850 species of bird. Arjan’s account of this year leaves the reader in no doubt about whether he had any such misgivings – his enthusiasm for birds and birding is evident throughout this book, and he clearly enjoyed himself very much indeed, for all there were the usual logistical bumps in the road familiar to anyone who’s gone birding off the beaten track. In the closing pages of the book he exhorts us to “stay optimistic about the future of the planet, adopt a positive attitude, and do your part.” On this note, Arjan explains that his global big year drew attention to many conservation initiatives, local guides and ecolodges, and raised almost 50,000 euros for BirdLife.

Arjan’s book, therefore, should be viewed as being part of his commitment to highlighting the wonder of the roughly 10,900 species of bird out there in the world, the places in which they’re found, and the people who work so very hard to conserve them against a rising tide of mounting human-induced pressures. He evidently wants people to care about these things.

Which leads us to the meat of the book – the account of the year itself. For the most part it’s told in the present tense, a growing vogue these days in nature writing. That’s not everybody’s cup of tea, of course. There are also digressions into Arjan’s past interspersed throughout the book, giving us some idea of the journey that formed him into the birder he is today. However, the main body of the book, told chronologically, is a sample of the highlights of his big year.

Inevitably, when one’s writing about a year in which one saw almost 7,000 species of bird, one can’t mention them all. Arjan presents his highlights here. Endangered, rare birds and countries blur together. There is spotlighting, playback, and a sense of constant birding effort. The pace is relentless, and it’s a little dizzying and unsettling to read, though perhaps that gives us a fair sense of how it was to experience such an intense and packed itinerary as that which Arjan undertook on his record-breaking mission.

There were some episodes that resonated more strongly for me – my modest South American birding experiences meant I could relate better to the tales of birds seen here. On the whole, however, I think rather like my own long-ago and considerably more modest year-listing experience, I ended up wanting to enjoy this book rather more than I actually did. That may say more about me and how I enjoy my birding these days than the book itself. Personally speaking, year-listing remains a thing of the past. It might well be an anachronism for other birders too.

Jon Dunn

Natural history writer, photographer and wildlife tour guide

Header photo: Jim Mathisen/USFWS

Suggested citation:

Dunn, J. Review of the book The (Big) Year that Flew By: Twelve Months, Six Continents, and the Ultimate Birding Record by Arjan Dwarshuis. Association of Field Ornithologists Book Review. https://afonet.org/2023/06/the-big-year-that-flew-by.

If you are interested in contributing a book review, or if there is a book you would like to see reviewed on our site, you can contact our Book Review Editor, Evan Jackson at evan.jackson@maine.edu