They say necessity is the mother of invention, and that was certainly true of our new method of selectively trapping songbirds. We didn’t set out to engineer a remotely closing door for a feeder trap — we just needed a way to capture some cautious House Sparrows.

The overall goal of this collaborative project is to find valid indicators of welfare in a common wild bird. I (Bonnie) work at Wild Animal Initiative, where we conduct research in wild animal welfare science, an emerging field of study that assesses wild animals’ valenced mental experiences (affective states such as pain, hunger, comfort, and pleasure). We ask what factors influence those affective states, how affective states affect the animals experiencing them, and what impacts they have on other organisms and the environment.

Scientists working with wildlife typically think about welfare only in terms of minimizing a study’s impact on its wild subjects. But research isn’t the only thing that affects how animals are feeling. In fact, the leading hypothesis for the evolution of subjective mental experiences like emotions is that they allow animals to modify their behavior to attain fitness-enhancing “rewards” and avoid fitness-reducing “punishments.” Animals base decisions on how they feel, rather than on complex calculations of costs and benefits. Perhaps this is because feelings are themselves the best approximation of those calculations: Affective states integrate internal and external factors, such as body condition, environmental circumstances, and social situations, and guide behavior based on their overall balance. Wild animal welfare science opens the door to studying affective states as part of animal ecology, much like stress physiology, immune function, microbiomes, and epigenetics. A key starting point is identifying measurable markers of welfare states.

For this House Sparrow project, I found collaborators with expertise that I don’t have, like Ben Vernasco’s decade+ of bird capture and handling experience. We set up feeding stations in backyards of the Houston suburbs. After a few months, House Sparrows were reliably coming to the feeders, so we thought trapping would be relatively easy. We were wrong.

Photo: Danielle Villasana

First, we put out ground traps near the feeders that were specifically designed to catch House Sparrows, leaving them baited and open so birds could habituate to them. But the House Sparrows avoided them entirely. We modified our IACUC protocol to include mist nets, but the sparrows avoided those, too, quickly changing course to fly just over them while other birds flew right in.

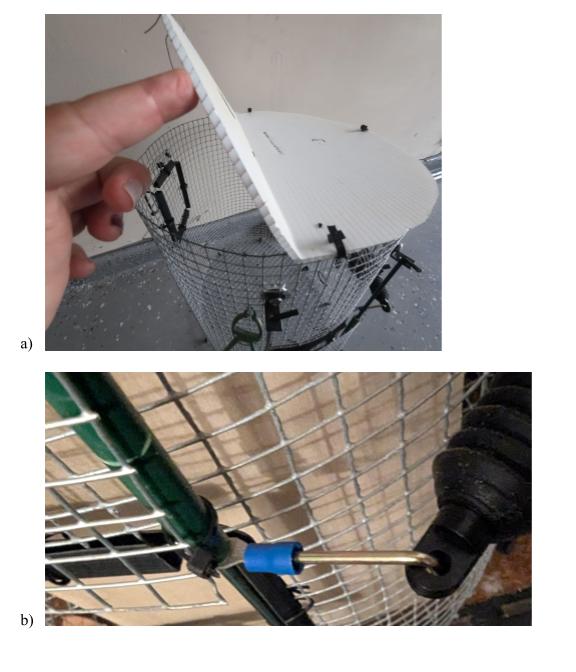

We decided to recreate traps that Ben designed as a post-doc. It used a fishing line to pull the doors of a circular feeder trap closed — Wile E. Coyote style! The design was inspired by Tree Swallow nest box traps. As you might have guessed, the House Sparrows refused to enter them despite the fact that the feeders they were habituated to were now inside the traps. It was clear that our risk-averse population needed time to habituate to these traps.

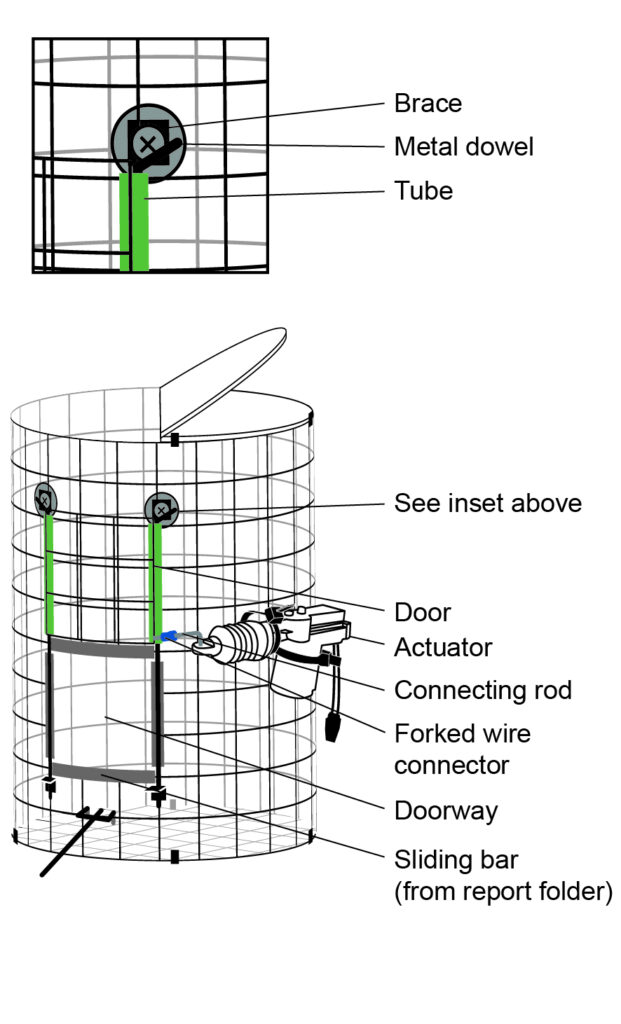

Before beginning habituation, I decided to modify the traps a little. I wanted the doors to be a little easier to close from a distance than pulling a string, which too often gets caught in foliage. I enlisted the help of my dad, who has a civil engineering degree and worked in construction his whole life. After much tinkering and repeated trips to the hardware store, we found a way to release the door so that it would drop under its own weight with the click of a button while we sat at a distance by using a remote car door lock.

I put out the traps several times a week, monitoring them either in person or via trail cams. After several months, five flocks showed signs of habituation. So an experienced assistant and I spent a week capturing birds. We went ahead and deployed the mist nets in the flight paths to the feeders too, since we wanted to be sure we caught at least a handful of House Sparrows.

In the end, we got 28 House Sparrows in hand. Six were caught in the traps themselves, and another 22 in the mist nets, which were in the flight path to the traps and somehow escaped the House Sparrows’ notice this time. But unlike the mist nets, the traps eliminated bycatch. They attracted plenty of non-target birds: Brown-headed Cowbirds were especially willing to enter the trap en masse, but we also found that Northern Cardinals, Carolina Chickadees, Chipping Sparrows, Savannah Sparrows, Scaly-breasted Munia, House Finches, Carolina Wrens, and Tufted Titmouses would enter the trap with little to no habituation. We even had a White-winged Dove squeeze in (and thankfully out of) the doorway, which was intended for smaller birds. These birds would have all ended up as bycatch that we needed to remove from the trap and release with a non-selective capture method, but instead they flew in and right back out, thanks to our control over the remotely closing door.

We hope you’ll give this trap a try if you’re trying to capture some but not all of the birds at your feeder station. You can modify the design, even just adding the door closing mechanism to traps you already have. Feel free to reach out if you have questions about constructing it, and let us know if it works for you.

Bonnie Fairbanks Flint

Wild Animal Initiative,

Virginia Tech Department of Biological Sciences

Text edited by Shannon Ray

The results of this study were recently published in the Journal of Field Ornithology:

Flint, B. F., and B. J. Vernasco. 2025. Bye-bye bycatch: a remotely closing trap for targeted songbird capture. Journal of Field Ornithology 96(4):8. https://doi.org/10.5751/JFO-00744-960408.

Header photo: House Sparrow (Passer domesticus) by Jay Brand | Getty Images/Pexels.